|

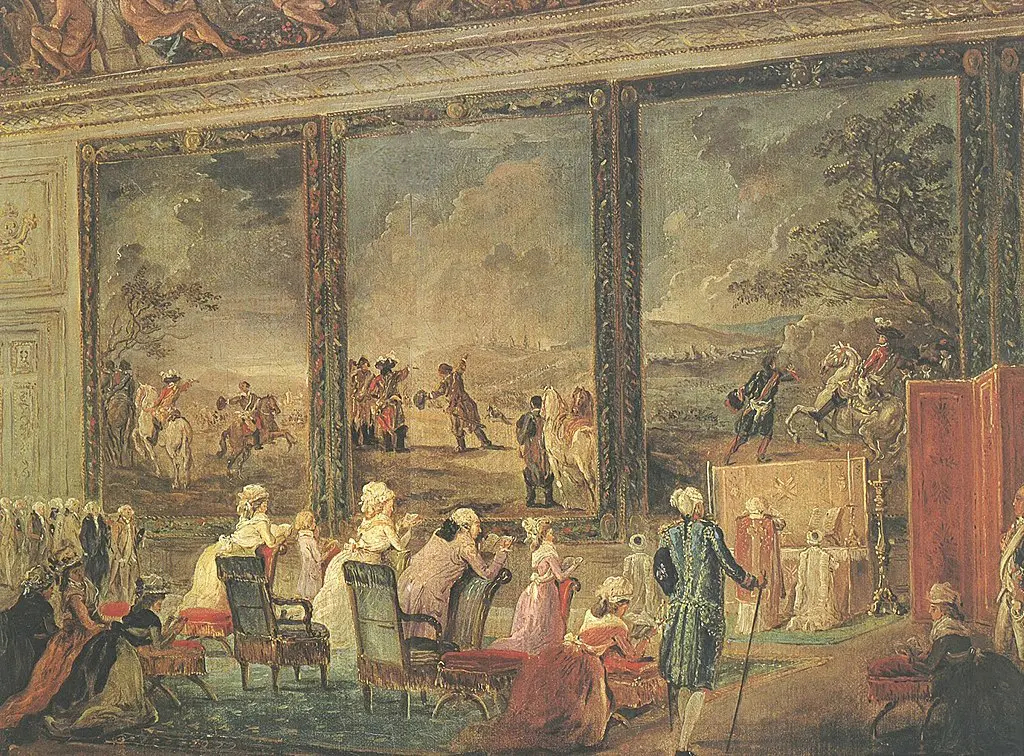

| Madame Elisabeth, Dauphin Louis-Charles, Marie-Antoinette, Louis XVI and Madame Royale assisting at Mass at the Tuileries |

From The European Conservative:

Such dislike, though, would be a mistake, because June has a much older and worthier title: the Month of the Sacred Heart. Not well known outside Catholic circles, devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus is in one sense as old as Christianity, when St. Longinus’ lance pierced it and out flowed blood and water, prefiguring Baptism and the Eucharist. In the Patristic and medieval eras, saints and mystics wrote of it, and of the salvific nature of the wounds and precious blood of Christ. In the latter period, these were ever more bound up with the growth of devotion to the Blessed Sacrament (and miracles arising therefrom) and the stories of the Holy Grail. It was under the banner of the Five Wounds that the Pilgrimage of Grace marched out against Henry VIII in defence of the Old Religion.

Our current version, though, dates back to the 17th century, with the revelations of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque. While bound up with making reparation to the Saviour who loves us so much, and suffered death to redeem us, the devotion from the beginning has had a social aspect. One of the requests made to St. Margaret Mary by Jesus was that Louis XIV consecrate his kingdom to the Sacred Heart and place the emblem on his flags and battle colours. This he did not do. But the devotion was taken up by many other royals: Queen Henriette Marie, consort of England’s Charles I; her daughter-in-law, Marie of Modena, James II’s queen; King Augustus I of Poland; King Philip V of Spain; Louis XV’s consort, Queen Marie Leczinska; her father, King Stanislaus of Poland, and her son, the Dauphin Louis; King Augustus III of Poland; Elector Maximilian III of Bavaria; SG Madame Elisabeth of France; her brother, King Louis XVI, who consecrated France privately to the Sacred Heart, and vowed to so publicly if he regained his throne; Maria, Queen of Portugal; King Charles X of France; Henri V, de jure king of France; SG King Francesco II of the Two Sicilies; Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary, and his wife Sophie; Bl. Emperor-King Karl of Austria-Hungary, and his wife, SG Zita; King Alfonso XIII of Spain; Albert I, King of the Belgians; Carlist heir Alfonso Carlos I; and a host of others down to the present.

Such counterrevolutionaries as the Vendeens, the Tiroleans under Andreas Hofer, the Spanish Carlists, and the Mexican Cristeros adopted it as their special badge. Garcia Moreno, president of Ecuador, consecrated his country to the Sacred Heart with its bishops in 1873. Following this, several Latin American countries began performing this national consecration: El Salvador (1874), Venezuela (1900), Colombia (1902), Nicaragua (1920), Costa Rica (1921), Brazil (1922), and Bolivia (1925). In Europe, Ireland’s bishops followed suit in 1873, Spain in 1919, and Poland in 1920. Across Europe and the world, shrines were dedicated in honour of the Sacred Heart—most notably that of Montmartre in Paris. In architecture alone, the Sacred Heart devotion has given the world a priceless treasure to be proud of, to say nothing of the stalwart folk who rallied around the emblem in defence of Christendom’s soul. (Read more.)

Once again, we try to make it clear that Marie-Antoinette never made a comment about cake, brioche, etc. And she was not a spendthrift but probably spent less than other queens, and definitely less than all the mistresses. From All That's Interesting:

ShareSome historians have suggested that revolutionaries caught wind of the quote “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche” from Rousseau’s writings, then falsely credited it to their despised queen as a form of propaganda. But even this does not hold up to modern scrutiny.

The earliest known source that connected the phrase to Marie Antoinette was the French writer Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr. In an 1843 issue of the journal Les Guêpes, Karr wrote that he found the quote originally in a “book dated 1760,” which he said meant that the rumor about Marie Antoinette must have been false, as she’d have been about five years old at the time the book was published. So, it’s very possible that the French citizens were indeed circulating the propaganda against the queen, though clearly not everyone was buying it.

Why, then, has the misquote carried on for nearly 300 years?

“It did not come to be misattributed to Marie Antoinette during the 18th century, but during the Third French Republic starting in 1870, when a careful program of reconstructing the historical past took place,” Denise Maior-Barron, an adjunct professor at Claremont Graduate University in California, told Live Science.

While the French Revolution of 1789 is considered to be the major revolution in France’s history, it is not the only time the French people rose up against their government.

Towards the end of the 19th century, France saw another major shift in power when members of the Third French Republic dethroned Napoleon III following his failed war against Prussia. Those same republicans then sought to effectively rewrite bits of France’s history to paint key figures in a different light — particularly, the disfavored queen Marie Antoinette.

“The masterminds of the French Revolution destroyed the French monarchy by continually attacking, and eventually destroying, its most important symbols: the king and the queen of France,” Maior-Barron said. “For this reason the ‘Let them eat cake’ type of clichés persist.” (Read more.)

No comments:

Post a Comment