Personally, I love aprons. And I loved my Betty Crocker Cook Book that I received for my sixteenth birthday. From Lit Hub:

ShareBetty Crocker’s Picture Cook Book is the best-selling cookbook in American history, with approximately 75 million copies sold since 1950. Not only did it guide generations of women in the kitchen; it was a cultural force, functioning as a blueprint for what it meant to be a good wife and mother. Cookbooks are one of those banal texts that we might ignore or dismiss, but this one, like so many others‚ tells a story about U.S food and everything that is wrapped up in it: family, power, class, culture, ethnicity, gender—and what it means to be American.

When eight-year-old Eleanor arrived to the US from Sicily in 1920, anti-Italian sentiment still gripped the nation.

“There was a lot of pressure for them to assimilate,” my grandmother said of her family. “My grandfather demanded that more than anything—if his wife slipped back into being too not American, or not American enough, he would remind her that that was important.”

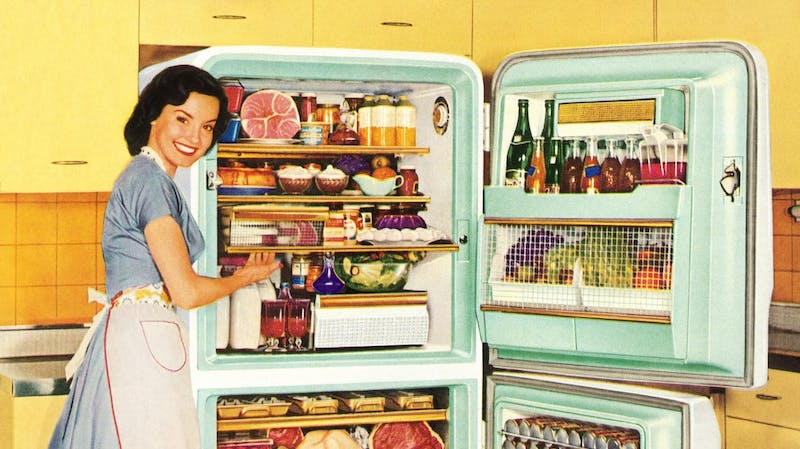

Her grandmother’s English was poor and heavily accented, and despite her dresses and high heels—“she looked like Betty Crocker,” my grandmother remarked—some people still stared at her as if she were “less than a human.” The family took pains to assimilate, and by the time my grandmother was growing up the message was clear: We are Americans.

Around the same time my Sicilian family arrived on the East Coast, Betty Crocker was “born” in Minneapolis to the Washburn Crosby company (what would soon merge with other milling companies to become General Mills). Betty’s birth had been something of an accident. In an advertisement for their signature product, Gold Medal Flour, Washburn-Crosby included a puzzle that readers could solve and send in for a prize. Much to the surprise of the all-male advertising team, thousands of women included letters alongside their completed puzzles, asking why their dough was lumpy or how to make their cakes rise.

The male employees were loath to sign their names to any letters in response, and so they invented a new name—Crocker for William G. Crocker, a recently retired executive, and Betty because they thought it sounded wholesome. After an informal contest among the women of the office to sign the letters, a secretary’s signature was chosen. With that, a handful of businessmen selling flour invented a fictional homemaker—and the perfect woman for the first half of the 20th century was born.

With the rise of radio in the early 1920s, Betty Crocker quickly became a star, with actresses and staff of General Mills bringing her to life on the airwaves. The arrival of World War II skyrocketed Betty to a new level of fame. General Mills distributed millions of pamphlets on the war effort, while Betty broadcast a message of community and patriotism on her widely popular radio show. In 1945, Betty Crocker was named the second-most influential woman in America by Fortune magazine—just behind Eleanor Roosevelt. At her height, she received as many as 5,000 letters per day. (Read more.)

No comments:

Post a Comment