skip to main |

skip to sidebar

From

The American Conservative:

When Tolkien published his massive three-volume trilogy, the masterful The Lord of the Rings, in 1954 and 1955, he was originally hoping to complete an even longer version, all in one volume. The hoped-for book would have been almost double the size of The Lord of the Rings and would include a fleshed-out version of The Silmarillion, to be called The Saga of the Jewels and the Rings. Those familiar with The Lord of the Rings know how often the stories of the Elder Days appear at critical moments in the trilogy.

When the Ringwraiths are about to attack the hobbits and Aragorn on Weather Top, the ranger tells the ancient and timeless story of Beren and Lúthien, almost as a preparatory prayer in anticipation of battle. Galadriel, in a moment of confession, admits she has lived in Middle-earth since before the fall of Gondolin. When Sam and Frodo wonder what their fate is as they approach Mount Doom, they compare their own experiences with those of a previous age, recognizing that they exist in the same story, just at a later time.

Indeed, the very phial of Galadriel, which proves critical in the suffocating darkness of Shelob’s lair, contains the very light that had first existed close to the time of creation itself. Truly Frodo and Sam occupy the same story as Beren and Lúthien. Yet Tolkien’s inability to finish the stories of the Elder Days, The Silmarillion, along with his exhaustion after 11 years of writing The Lord of the Rings, frustrated his own desires. Additionally, the British government continued to impose its own wartime restrictions on paper, even into the 1950s. Tolkien’s publisher had originally wanted and expected a sequel to The Hobbit, not an epic covering thousands and thousands of years, written with the depth and feeling of The Aeneid.

Even after the successful publication and critical reception of The Lord of the Ringsand his own retirement from teaching, Tolkien found it painful to finish The Silmarillion and his own mythology. He often spent his time instead on questions best left to his publisher and writing gorgeous essays on the philosophical and theological implications of his created world.

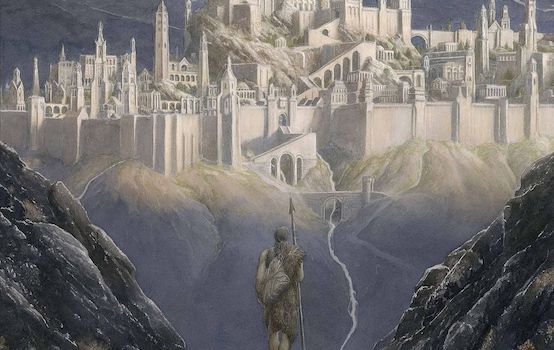

It would take Tolkien’s son, Christopher, four years after his father’s death to compile and publish The Silmarillion. Even then, in 1977, it remained more a beautiful outline than a true representation of the early mythology. From there, though, Christopher’s output was nothing short of stunning. In 1980, he published Unfinished Tales and, between 1983 and 1996, the 12 volumes of The History of Middle-earth, a massive undertaking of love and piety. Silent for almost a decade, but infuriated by the travesty of the Peter Jackson movies, Christopher reappeared in the publishing world, hoping to reclaim his father’s ideas, words, characters, and stories for an audience desiring more than action sequences and computer generated eye candy. He hoped an audience for poetic wonder still existed, even in the 21st-century wasteland of modernity. Over the last 12 years, Christopher has come back with a vengeance, publishing his father’s scholarly work on his many varied mythologies as well as specific stories from The Silmarillion, but, most notably, the three that mattered most to his father: the tale of Beren and Lúthien, The Children of Húrin, and, as of last fall, The Fall of Gondolin.

As with the other books that Christopher has edited, this latest Tolkien release, The Fall of Gondolin, follows the chronological evolution of J.R.R. Tolkien’s various tales. As always, Christopher offers not just the chronology but an insightful examination of why his father chose this or that, as opposed to that or this. Presumably, The Fall of Gondolin is the son’s last, though not all of the father’s writings have yet seen print. (Read more.)

Share

No comments:

Post a Comment