|

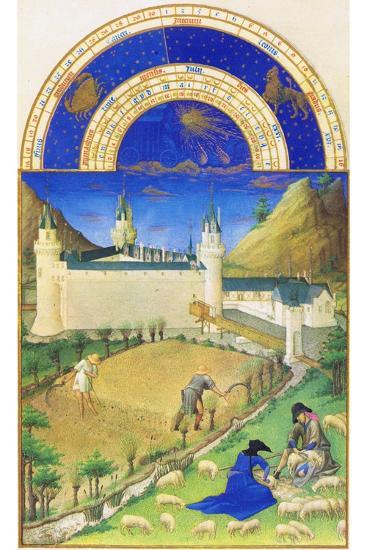

| From the Book of Hours of the Duc de Berry |

|

| Astronomical Clock in Padua |

If you ever wondered why zodiac signs often appear in old missals and breviaries (books of hours), in medieval art and on Renaissance clocks, it is because, while the Church bans divination and fortune-telling, it has never banned what is called "natural astrology" which, for most of the history of the world, was counted among the sciences. It is why many saints such as St. Hildegard, St. Thomas Aquinas, and St. Albert the Great, whose feast is today, and other holy persons, referred to the zodiac in their medical writings and "scientific" treatises. From Marina Marchione at Darkstar Mythology:

For much of history, the study of the stars was not a mystical art, but a science. The same doctors who tended the sick and studied anatomy also charted the movements of the moon and planets. To a medieval physician, the heavens and the body were woven together in one great pattern of divine design. Understanding that pattern was seen as an act of reverence for the Creator, not a defiance of Him.

In the great universities of the Middle Ages — Paris, Bologna, Oxford — medical students learned both astronomy and astrology. Astronomy meant the measurement and geometry of the heavens: how the moon moved, how eclipses worked, and how to calculate the calendar. Astrology meant understanding how those heavenly rhythms affected life on earth — weather, crops, tides, and the human body.

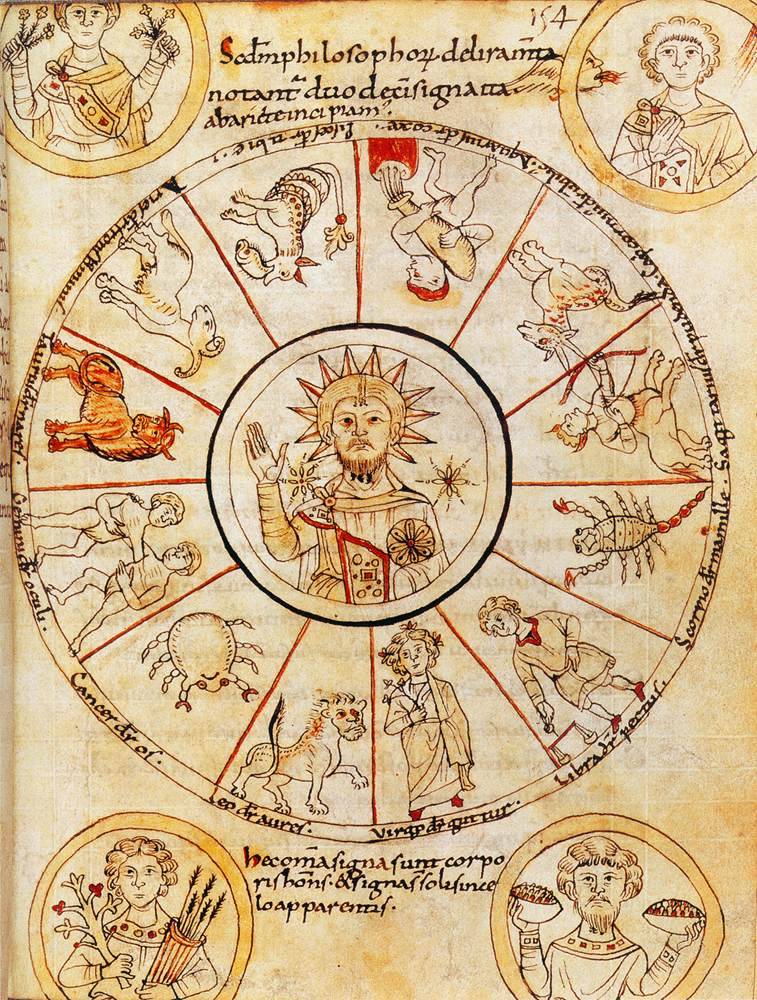

The body itself was believed to reflect the cosmos. Medieval manuscripts often show the “Zodiac Man,” a figure mapped from head to foot with the twelve signs: Aries ruling the head, Taurus the neck, Leo the heart, Pisces the feet.

The moon’s monthly journey through those signs guided physicians in their timing of treatments. They believed that when the moon was passing through the sign that governed a particular part of the body, that area was more “sensitive” — so operations or bloodletting were best avoided then.

This was not superstition to them, but science — an attempt to work with the rhythms of nature rather than against them. Their calendars of moon phases and star signs were tools for health, just as stethoscopes are today. (Read more.)

|

| Illuminated manuscript on parchment, c. 11th century. Collection: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris |

No comments:

Post a Comment