The history and philosophy behind the film. [NOTE: I have not seen it.] From Wired:

EARLY IN THE morning of July 16, 1945, before the sun had risen over the northern edge of New Mexico’s Jornada Del Muerto desert, a new light—blindingly bright, hellacious, blasting a seam in the fabric of the known physical universe—appeared. The Trinity nuclear test, overseen by theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, had filled the predawn sky with fire, announcing the viability of the first proper nuclear weapon and the inauguration of the Atomic Era. According to Frank Oppenheimer, brother of the “Father of the Bomb,” Robert’s response to the test’s success was plain, even a bit curt: “I guess it worked.”

With time, a legend befitting the near-mythic occasion grew. Oppenheimer himself would later attest that the explosion brought to mind a verse from the Bhagavad Gita, the ancient Hindu scripture: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.” Later, toward the end of his life, Oppenheimer plucked another passage from the Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” (Read more.)

From Ars Technica:

Nearly 70 years after having his security clearance revoked by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) due to suspicion of being a Soviet spy, Manhattan Project physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer has finally received some form of justice just in time for Christmas, according to a December 16 article in the New York Times. US Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm released a statement nullifying the controversial decision that badly tarnished the late physicist's reputation, declaring it to be the result of a "flawed process" that violated the AEC's own regulations.

Science historian Alex Wellerstein of Stevens Institute of Technology told the New York Times that the exoneration was long overdue. “I’m sure it doesn’t go as far as Oppenheimer and his family would have wanted,” he said. “But it goes pretty far. The injustice done to Oppenheimer doesn’t get undone by this. But it’s nice to see some response and reconciliation even if it’s decades too late.”

Oppenheimer was born in New York City to German Jewish immigrants and studied physics under Ernest Rutherford at Cambridge, before earning his PhD from the University of Gottingen in 1927 under Max Born. He eventually joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the Manhattan Project and tapped Major General Leslie R. Groves to head it, Groves in turn chose Oppenheimer to lead the secret weapons laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico. True, Oppenheimer had left-wing political views, and hadn't won a Nobel Prize (although he was nominated several times). But Groves felt the physicist had the breadth of knowledge to bring together physicists, chemists, engineers, and metallurgists, among other disciplines whose expertise would be crucial to the success of the project. (Read more.)

|

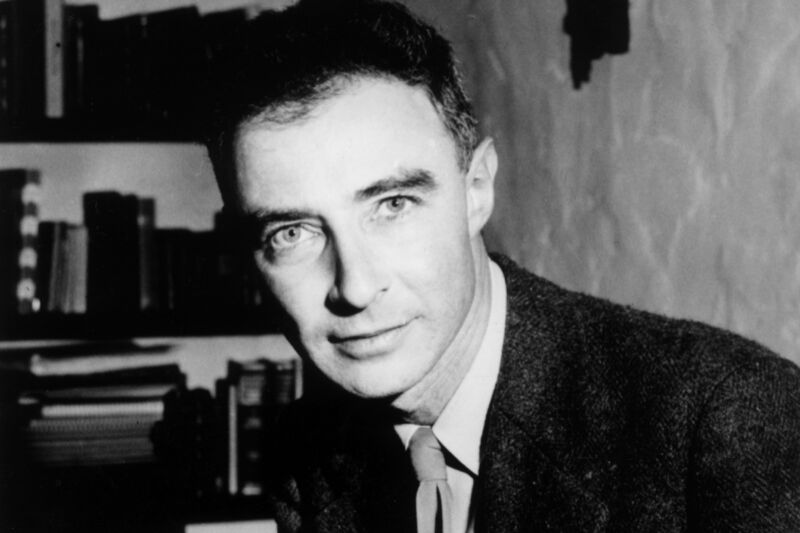

| J. Robert Oppenheimer |

From The American Thinker:

Hollywood really does seem to be running out of new ideas. British big-budget director Christopher Nolan had his successes a few years ago with yet another round of Batman movies, but his expensive, visually lavish, films have otherwise not drawn large audiences.

His new release, about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist who helped build the first atomic bombs, seems very much just another thin remake of a story long told. It is based on a 17-year-old book, American Prometheus, that was itself started way back in 1980. The late Cold War era featured miniseries, movies, documentaries, and plays all about the gang at Los Alamos., Although we have learned quite a bit more about the real Oppenheimer and the atomic spies, thanks to the opening of Kremlin files with the fall of the Soviet Union, Hollywood and the establishment media won’t go anywhere near any of that.

Instead, they are stuck in a late 1970s redux, where the Manhattan Project is a kind of X-Men comic adventure. Oppenheimer, the wise, sensitive leader, is Professor X, of course. A man learned in advanced physics and the Bhagavad Gita, so he can say cool things like “I am become death, destroyer of worlds” when a plutonium bomb explodes. He leads a band of genius scientists, harnessing forces too powerful for ordinary men to understand, and is beset by reactionary right wingers, who would misuse his discoveries. Especially those who did not understand the atomic bomb was only meant to stop Hitler and must not lead to America becoming too powerful and doing dangerous stuff, like, insisting on democracy for Eastern Europe and Russia after the war. That’s the basic story Hollywood keeps retelling.

The reality was quite different. The guy in charge was Leslie Groves, an Army engineer. He was the one who set up the whole Oak Ridge secret city, that produced the crucial fissile material and made the bomb possible. Something neither the Brits nor the Germans had the resources to ever do and the Russians only later on, when they had enough stolen secrets. (Read more.)

From VoegelinView:

Nolan’s most recent work, Oppenheimer, starring Cillian Murphy, Matt Damon, Robert Downey Jr, and Emily Blunt (among a host of other stars), has been receiving rave reviews across the board. Although outperformed at the box office by Barbie, which was released the same day, Oppenheimer is on track to be another Christopher Nolan success and is sure to garner multiple Oscars. Like Tenet, the film is, on one level, about theoretical physics—although Oppenheimer is much more comprehensible and coherent than Tenet. It is also a film, like much of Nolan’s other work, that subtly celebrates liberal democratic America as being essentially superior to its political competitors (Nazism and Communism). Moreover, the film is about a tormented and ethically complicated individual who attempts to create a world for himself and others and whose family must pay the price for his craft.

Critics have rightly praised Cillian Murphy’s performance as Robert J. “Oppie” Oppenheimer. There is little doubt that Murphy has achieved the quintessentially postmodern feat of creating a fictional character whose pathos and powerful will define (and perhaps even overshadow) the real historical figure. Matt Damon is excellent as Lt. Gen Leslie Groves as is Robert Downey Jr. as the vindictive and power-hungry rival to Oppenheimer, Lewis Strauss. The film is tightly edited, but, as some critics have complained, drags out in its third act, testing the audience’s patience. Three hours is a long film, even for a blockbuster.

There are two key pieces of dialogue in the film that provide a map to understanding its intellectual structure. The first is when Oppenheimer explains that the weakness of the Nazis against which they are competing is their anti-Semitic prejudice. Adolf Hitler infamously denounced quantum physics as “Jewish science,” hamstringing the German science effort. America, in contrast, is a (relatively) more free and meritocratic society in which people of a host of cultures and ethnicities can excel. This philosophy has undergirded much of Nolan’s implicit political philosophy in his films. In the Batman Nolanverse, a host of characters such as Batman Begins’ Ra’s al Ghul, The Dark Knight’s Joker, and The Dark Knight Rises’ Bane have all challenged the dominate Anglo-American order (represented by Gotham); however, Gotham’s heroes always (albeit sometimes reluctantly) fight to protect that order and eventually triumph. Similarly, in Oppenheimer, despite the flaws of the American military and political establishment, the United States of America is better than the threatening alternatives of Soviet Communism and German Nazism even if this is somewhat passé in contemporary intellectual circles, especially online and in elite universities. America is imperfect, yes, but is still good and better than the rest.

ShareThe second key piece of dialogue in the film occurs when Murphy’s Oppenheimer explains to a woman the nothingness that lies at the heart of existence according to certain strands of theoretical physics. This nothingness is present in all of Nolan’s films, but, in Oppenheimer, as in Dunkirk, it eats away at too much of the film. Nihilism is now at the forefront of the film. No figure represents nihilism more than Oppenheimer himself. On one level Nolan celebrates Oppenheimer as a dashing and brilliant intellectual who (like Nolan himself) achieved fame and fortune in the United States. In the film, Oppenheimer pushes the Trinity Project to success, rides horses across through the New Mexico desert with a beautiful woman, reads T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland and savors other elements of European High Modernism (showing him as a cultured man saving the best of western culture), stands up to Nazism, sweeps multiple women off their feet, clashes with the American military establishment, raises a family, mourns the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and ultimately becomes an advocate for world peace and arms control. Nolan’s Oppenheimer is a loyal friend and advocate for workers rights, while, in Nolan’s reading, remaining loyal to America and avoiding the pitfalls of communism. Nolan’s Oppenheimer is the nihilist superman, a man driven to success in an ultimately empty universe of nothingness by sheer force of will. (Read more.)

No comments:

Post a Comment