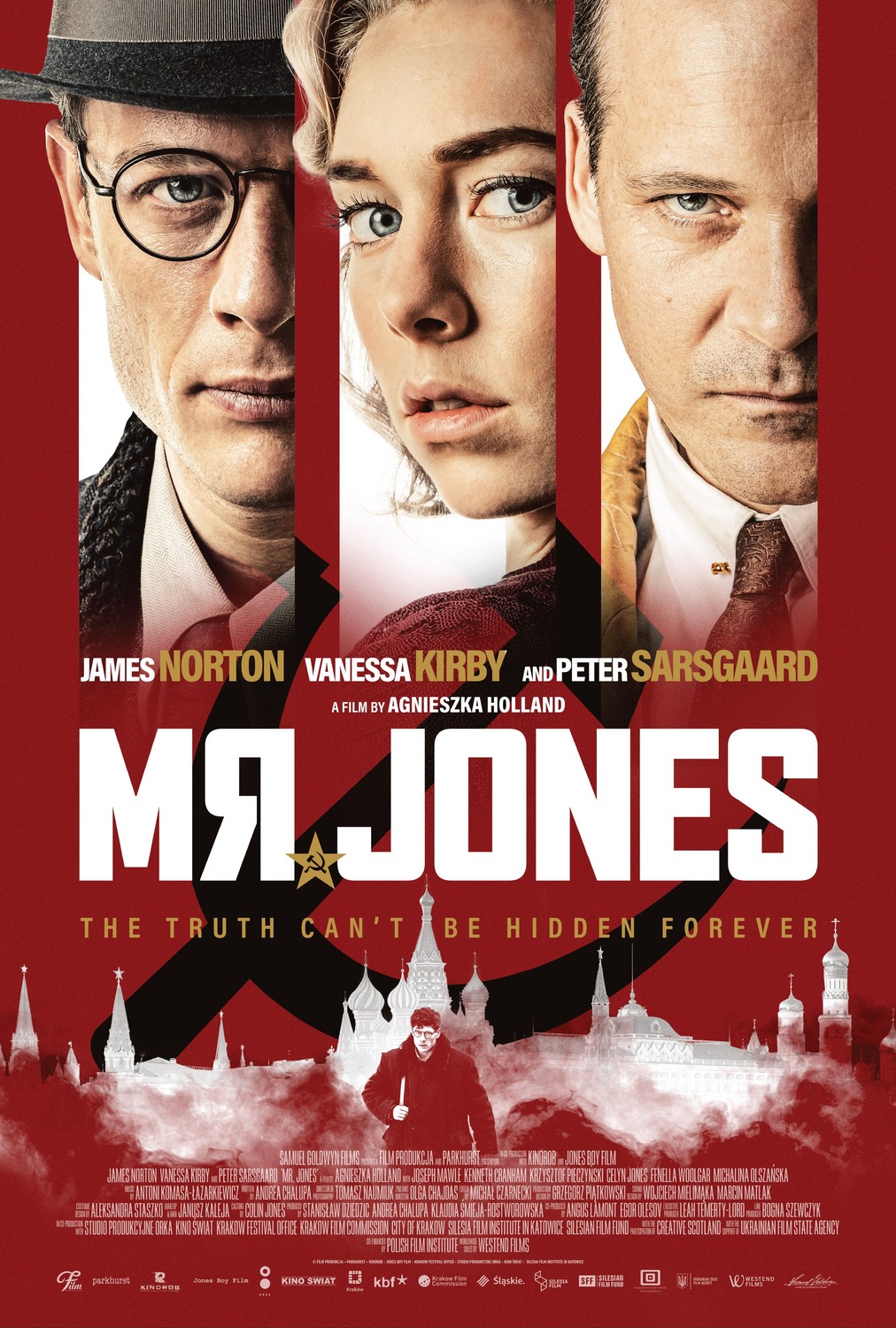

Directed by the Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland and written by the journalist and author Andrea Chalupa, the film establishes its tone and theme quickly. The year is 1933. Gareth Jones, played marvelously by James Norton, is a British Foreign Office worker who has just interviewed Adolf Hitler on a private plane. Jones is convinced Hitler presents a worldwide threat—“world history would have changed” if Hitler’s plane gone down, he later muses—but he is scoffed at by former Prime Minister David Lloyd George (Kenneth Cranham). Jones is a zealous truth-teller. Shortly after the Hitler scoop, he finds himself out of work due to budget cuts. Back home, he begins to doubt the official narrative about the growth of the Soviet economy. Jones asks a simple question: where is the money coming from? Stalin’s claims about the new, booming Russia don’t match up with the starving witnesses on the ground. Jones lobbies Lloyd George to send him to Russia to meet with the dictator. When he is refused, he goes himself as a stringer for the Western Mail.

Once in Moscow, Jones realizes that Stalin’s collectivization is a fraud perpetrated by a criminal government and propped up by sympathetic journalists from the West. These include one Walter Duranty, the oleaginous, established correspondent for The New York Times. Duranty is played to slimy effect by Peter Sarsgaard, who coincidentally also played Charles Lane, the editor of the exposed New Republic fabulist Stephen Glass, in Shattered Glass (2003). Duranty strikes entire pages of copy that don’t uphold the official Soviet view. The journalist Joseph Alsop once called Duranty a “fashionable prostitute” for the Bolsheviks, and to British writer Malcolm Muggeridge, who was blackballed by many British newspapers after reporting the truth from Russia, Duranty was “the greatest liar of any journalist I have met in fifty years of journalism.” But the Soviet sympathizer won a Pulitzer Prize in 1932 for his exclusive interviews with Stalin. To defend everything from mass starvation to the show trials of 1928, 1934, and 1936, Duranty had a simple response, parroting Robespierre: “You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” (Read more.)

Arriving in Russia, Jones’ wide-eyed blend of naivety and stubbornness gets a rude awakening when he meets Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times journalist Walter Duranty (Peter Sarsgaard). In the pocket of the Stalin regime, Duranty lives a life of spoiled, Jazz Age excess, writing and editing pro-Russia pieces by day, and enjoying hedonistic, drug and sex-fueled parties by night. Unable to get the help he needs from Duranty, Jones turns to Ada Brooks (Vanessa Kirby), a writer in his stable, who knows more about the rumors than she’s initially willing to divulge. She’s a firm believer in Russia’s Great Experiment, but eventually, her resolve weakens enough to guide Jones toward the Ukrainian countryside where he’s quickly greeted with the monstrous realities of the Holodomor.

Out of the gate, “Mr. Jones” feels exhumed from another era, like a lost film from the late-‘80s and early-‘90s, where this kind of determined, staid, and talky picture would’ve been familiar among the mid-budget offerings studios routinely made at the time. In 2020, Holland’s picture initially seems a bit of a novelty, but it quickly becomes evident how the filmmaker’s well-honed craft and the strong efforts of her technical and design team elevate the straight-forward script by first-time Andrea Chalupa. Working with cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk (“High Life”) and production designer Grzegorz Piatkowski, the early stages of the film soak up the richness and opulence of London and Moscow upper-crust circles, all amber lighting, oak-lined rooms, and cigar smoke ambiance. These carefully arranged vignettes of affluence later work to strike a nauseating chord in the film’s third act, as Jones returns home, reeling from the unimaginable discoveries he’s made among the agricultural peasants suffering under Stalin’s thumb.

It’s the middle of “Mr. Jones” that truly displays Holland’s sturdy

command of the material, and the ability of her collaborators to rise to

the challenge. The picture shifts from procedural to something akin to

an atmospheric horror film, as Jones traverses across an unforgiving,

barren, bleak landscape, visiting one desolate and desperate small

village after another, where hunger has driven an untold number to

madness and death. The film slows here, and takes the audience on a

journey of emotional and physical survival, providing an understanding

of this little talked about famine that’s experiential. A strong factor

in the success of this crucial second act is due to Norton, who gives a

committed performance that portrays Jones’ dedication to a cause as both

admirable and reckless. (Read more.)

The man in question is Gareth Jones (James Norton), an adviser to David Lloyd George (Kenneth Cranham), formerly the British Prime Minister. It is the early nineteen-thirties, and Jones is met with condescending mirth when he tells a group of graying British high-ups that Hitler is intent on war. Jones, however, knows whereof he speaks; he interviewed the Führer, on a plane, and, for his next scoop, he hopes to talk to Stalin. He therefore travels to Moscow, as an independent journalist, and although the interview never happens, the dogged Jones remains perplexed by the boom in Soviet industry. How is it being funded? “Grain is Stalin’s gold,” he is told. And where is much of the grain traditionally reaped? Ukraine. So that is where Jones goes. As Lloyd George said of him, “He had the almost unfailing knack of getting at things that mattered.”

What matters in “Mr. Jones” is the Holodomor, the famine that befell Ukraine in the years 1932-33. Current scholarship estimates that just under four million people died. They did not pass away from natural causes. The best and the most detailed English-language study of the subject is “Red Famine,” a 2017 book by Anne Applebaum, who demonstrates that starvation was a deliberate policy, enforced by Stalin through the requisition of crops and other products and the widespread persecution, deportation, or even execution of the non-compliant. His grand scheme of collectivized farming had failed, as any local farmer could have predicted, yet it was not ideologically allowed to fail. Who better than the Ukrainians, so often distrusted and demonized by Moscow, to be cast as scapegoats and saboteurs?

Dramatizing a theme of such enormity is a test for any filmmaker. Holland’s response is threefold. First, she shadows virtually every scene with a distorting darkness, as if prophesying doom, long before the action reaches Ukraine. Second, she introduces none other than George Orwell (Joseph Mawle) as a framing device. At the outset, we find him at work on “Animal Farm,” the implication being that the novel—which boasts a Mr. Jones, a farmer, in the opening sentence—was inspired, or informed, by what we are about to witness. (A curious move; if, as a film director, you have faith in the strength of your narrative, why should it need an extra boost?) Later, the link is made explicit, as Jones, returned from his mission, is introduced to Orwell, though whether such a meeting ever took place is open to debate.

Holland’s third tactic, as Jones journeys through the blighted landscapes of Ukraine, is to show us only what he sees, in the hope that a deep note of universal suffering will resound through the particular. Thus, when Jones eats an orange on a train and discards the peel, his fellow-passengers lunge and scrap for the nutritious prize. Alighting at a secluded railroad station, he passes a body on the platform. Lying there, frozen and unremarked, it is meant to represent the innumerable dead who are strewn around the countryside like litter. The same goes for the scene in which a baby, though still alive and crying, is tossed onto a cart with the already deceased, to save time; or the lumps of meat that are cooked and eaten by children, having been cut from the remains of their brother.

None of these monstrosities are inflated. Applebaum’s book includes a lengthy section on cannibalism. (Some parents consumed their offspring, survived, and, having woken to the realization of what they had done, went mad. By then, they were in the Gulag. How much hell do you want?) In a feature film, though, isolated horrors are liable to come across as eruptions of a foul surrealism rather than as testamentary evidence, and we don’t—or can’t—always make the imaginative leap in scale. When Jones himself grows famished, and chews in desperation on tree bark, we are scarcely moved, for the plight of one outsider, from the well-fed West, is of no consequence in the apocalypse of hunger. (Read more.)

No comments:

Post a Comment