Helen by Canova

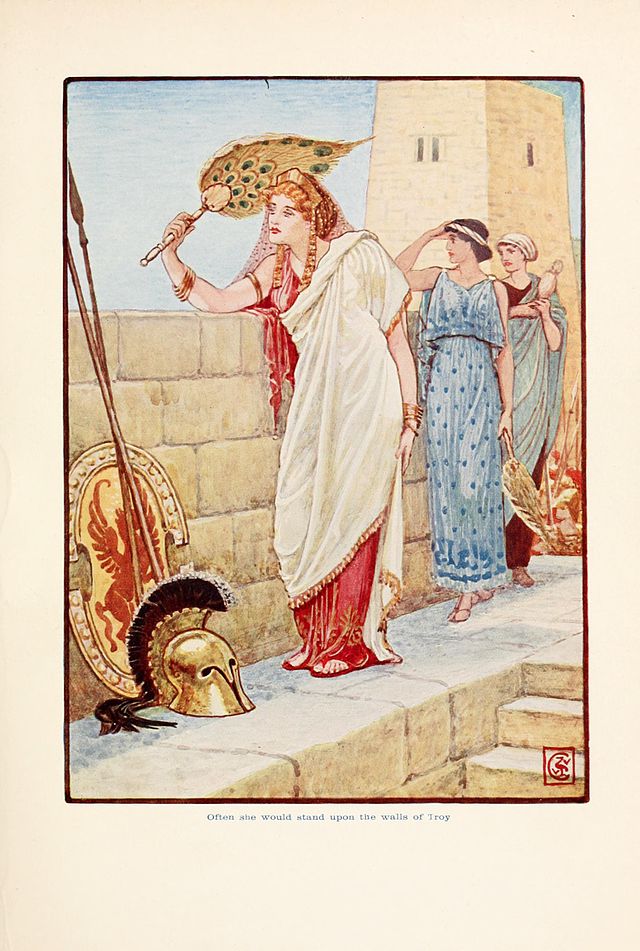

Helen on the Walls of Troy The face that launched a thousand shipsAnd burnt the topless towers of Ilium.—From The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus by Marlowe

From Ancient History Encyclopedia:

Helen of Troy (sometimes called Helen of Sparta) is a figure from Greek mythology whose elopement with (or abduction by) the Trojan prince Paris sparked off the Trojan War. Helen, considered the most beautiful woman in the world, was the wife of Menelaus, the king of Sparta, and he persuaded his brother Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, to form a great army to besiege the mighty city of Troy in order to recapture Helen. Following the Greek victory in the war, Helen returned home with Menelaus but she became a despised figure in the ancient world, a symbol of moral failure and the perils of placing lust above reason. Despite the poor standing of the literary Helen, she also had a divine form and was the centre of cults at several Greek sites, notably Rhodes, Sparta, and Therapne.

In Greek mythology, Helen was the daughter of Zeus and Leda, the queen of Sparta and the wife of Tyndareus. Zeus disguised himself as a swan to seduce Leda, and Helen was the result of their amorous engagement. In another version of the myth, Helen's mother is the goddess Nemesis, the personification of retribution. Whoever is the mother, in both versions, Helen is born from an egg in Sparta. Helen's siblings included the hero twins Castor and Pollux (aka Polydeuces) and Clytemnestra, the future wife of King Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae. One day, Tyndareus offered sacrifices to all the gods but forgot Aphrodite and the goddess, angered at the slight, then promised that all of the king's daughters would become infamous for their adultery. (Read more.)

From The New Republic:

Ruby Blondell’s insightful study of ancient Greek representations of Helen of Troy notes the close connections between her subject and the Pandora myth. Both, she argues, spring from cultural anxieties about female beauty and female sexuality, centered on the figure of the parthenos—the girl at marriageable age, a liminal figure who must cross from the world of childhood in her father’s house to the house of her husband. “She must be sufficiently reluctant to suggest that she will not stray once she is married, but she must also actively desire her new husband”—a balance that constantly threatens to tip over. Helen, the most famous adulterous wife in the Western tradition, is figured as a woman who is constantly in this liminal state, and who repeatedly crosses over from one household to another: “many-manned Helen,” as Aeschylus calls her. She was (and is) the locus for exploring the questions of whether beautiful women are always necessarily bad, and whether female sexual desire is always a force of destruction. She is also—unlike modern versions of the promiscuous or adulterous woman—always presented as at least semi-divine, the ever-young, ever-beautiful daughter of Zeus, worshiped at cult centers all over Greece, especially in her native Sparta. Modern versions of misogyny usually do not account for the possibility that “bad” women might also be goddesses.

The best-seller about Helen of Troy by the television presenter Bettany Hughes, from 2007, bizarrely claimed to tell, and to celebrate, “Helen as a real character from history,” while acknowledging that her existence is only “a possibility”—as if the biography of a mythical character from three thousand years ago could possibly be reconstructed. Blondell has almost none of this naïveté: she notes explicitly that her subject is a set of cultural tropes, not a historical person. Helen was a construction of the Greek male imagination, and the myths and literary treatments of Helen can teach us nothing about the lives even of women in classical Greece, let alone women in Sparta in the Bronze Age: she is “a concept, not a person.” But these myths can teach us a great deal about the complex attitudes of ancient Greek men, mostly ancient Athenian men, toward women, female beauty, and male desire.

The story goes that Zeus wanted to reduce the human population, so he arranged for the birth of the two characters who would make the Trojan War inevitable: Achilles and Helen, representing “seductive female beauty and destructive male strength.” They have in common an extraordinary self-awareness and concern for their future reputations in myth and legend. Both were half-human, half-divine, Achilles being the son of the mortal Peleus by the sea-goddess Thetis, and Helen the daughter of Zeus in the form of a swan and of the Spartan queen Leda. Owing to this parentage, she hatched from an egg—the first mark of her unusual, not-quite-human status. Helen is the only female child of Zeus by a mortal woman, an exceptional woman in this as in every other respect. Other versions of the myth suggest that she was the daughter of Nemesis, or “Destruction.”

Helen’s beauty is not subjective. A key premise of the myth is that she is beautiful in some absolute and total way that defies description, and hence can be represented only by entirely conventional means. Helen, like any other beautiful woman in the Greek literary tradition, has lovely cheeks, neat ankles, and pretty accessories. She is equally irresistible to any and every man. As Blondell neatly puts it, “a beauty that is in the eye of the beholder may launch a ship or two, but only a beauty upon which all beholders agree can bind a generation of heroic males under oath and generate an enterprise as cataclysmic as the Trojan War.”

From a young age, Helen was prone to getting abducted. When she was still a young girl the Athenian hero Theseus swiped her, but she was retrieved by her magical brothers, the twins Castor and Pollux. A little later, suitors from all over Greece began to court her, and took an oath that they would all fight together for her eventual husband. Menelaus of Mycenae, whose main claim to fame was his wealth, won Helen as his wife. But some time afterward, a Trojan prince named Paris was appointed to judge between three goddesses, Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite. He chose Aphrodite, goddess of love, because she promised him Helen as a reward—the only problem being that Helen was married already. The abduction of Helen caused the Trojan War. (Read more.)

|

| The Hatching of Helen |

| ||||

| Giampietrino, after Leonardo, Leda with her Children: Castor and Pollux, Helen and Clytemnestra |

| ||||||

| Abduction of Helen by G. Hamilton | |

More HERE.

|

| Helen with King Priam watching Menelaus fight Paris |

2 comments:

I've never felt that Helen is an attractive or warm personality in Homer or the Greek plays. No doubt fascinating, intelligent and physically very beautiful but not particularly sympathetic. She seems quite self-serving and manipulative.

She's an archetypal male fantasy.

Post a Comment