Anyone who is interested in sacred art and beautiful writing should subscribe to The Sacred Images Project. From Hilary White:

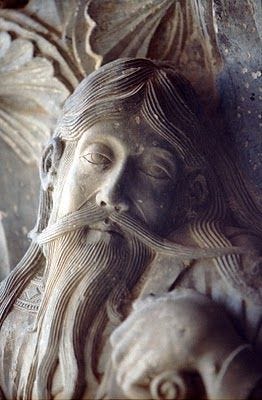

Why do these faces feel at once so strange and so compelling? However abstract or otherworldly they appear, we are caught by them; their gaze captures ours. They seem to defy our ideas about what sacred art is for; they do not invite us into a personal, interior, intimate moment. We feel silenced when looking, as if we are being in turn looked at, from an unimaginable distance.

We call it “Romanesque” today but this is a much later academic nomenclature; a term from academics of the early 19th century, whose attention was always trained on Imperial Rome. They saw the architecture, the barrel vaults, rounded arches and solid stone construction, as a “revival” of Roman imperial greatness. But this label risks obscuring the deeper and more immediate roots of the style in monastic liturgy, Christian cosmology and the symbolic imagination of the Middle Ages - all greatly despised by 19th century “men of reason”.

Much later, post-Christian scholars may have named it “Romanesque” but at the time it wasn’t a conscious revival of Classical Antiquity; medieval men would probably have thought that ancient, Classical pagan Rome deserved its fate for murdering the saints. The churches, paintings and sculptures of the eleventh and twelfth centuries were shaped by the practical and spiritual needs of a new Western Christian society, defined by Benedictine monasticism, growing pilgrimage networks and a theology that prioritised symbolic meaning over naturalistic representation. When we talk about early medieval western sacred art, we’re talking about Romanesque.

In the Romanesque, the human faces and figures of Christ, the Virgin, the saints and angels were not painted to resemble any specific individual. Far from it. These are faces abstracted sometimes almost out of recognition into stylised, linear geometric forms intended to express visually the eternal mysteries. In manuscripts, frescoes and sculpture, these faces served as symbols: condensed signs of a humanity transfigured by divine life. (Read more.)

No comments:

Post a Comment