|

| Russian portrait miniature of Marie-Antoinette |

|

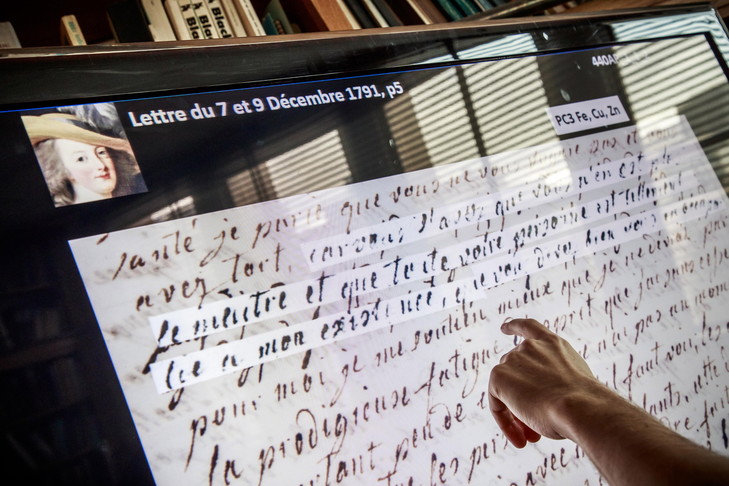

| Fabien Pottier decrypts a letter of Marie-Antoinette |

Love letters between the ill-fated French queen Marie-Antoinette and her lover, which contain key passages rendered illegible by censor marks, have been deciphered using new techniques, the French National Archives said yesterday. The revealed passages are further confirmation of the steamy relationship between Marie-Antoinette and Count de Fersen, who were writing to each other two years after the 1789 French revolution. At the time, the queen and King Louis XVI were living under surveillance in the Parisian Tuileries palace and had just failed to escape their house arrest. Much of the lovers' correspondence had already been brought to light, but redacted lines remained illegible. Until now.The first paragraph is full of falsehoods. Fersen has not been proven to have been Marie-Antoinette's "lover" in the full sense of the word, and the letters are not "steamy" but overwhelmingly political. It is indeed irresponsible and misleading to refer to them as "lovers." The Swedish nobleman was in the service of his sovereign King Gustavus III and Count Fersen’s presence at the French court needs to be seen in the light of that capacity. The Swedish King was a devoted friend of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette and Gustavus, even more than the Queen’s Austrian relatives, worked to aid the King and Queen of France in their time of trouble. Fersen was the go-between in the various top secret plans to help Louis XVI regain control of his kingdom and escape from the clutches of his political enemies. In fact, by late 1791, when the letters in question were written, Fersen had already helped the Royal Family escape, only to have them disastrously recaptured at Varennes in June of the same year. Fersen saw his failure as not only endangering the lives of his dear friends, but also the destruction of what would have been the glory of his career, to have been the one responsible for the rescue of the French royal family.

“For the first time we can read Fersen's writing using unambiguous sentences on his feelings for the queen, which had been carefully hidden,” said the REX project's leaders in a statement. “Marie-Antoinette and Fersen express themselves using the terminology of love, even if the majority of the content of the letters is political,” the statement added.

The 95-day project used a two-year-old scanning technique — the X-ray fluorescence system (XRS) — to analyse the composition of the inks used.

“The principal conclusion of the REX project is less about sensational revelations on the relationship between Marie-Antoinette and Fersen, and more about the expression of feelings of hope, worry, confidence and terror, in a particular context of forced separation and imprisonment,” said the statement. Similarities between the ink used by the count and the ink of redaction suggest Fersen may have censored his own letters. Out of the 15 redacted letters written by Marie-Antoinette and Fersen, only the content of 8 was brought to light. For the others, the ink used to write and to censor was the same, rendering the task of revealing the redacted content impossible. (Read more.) [Bold text is mine.]

Although Marie-Antoinette might have been in love with Count Axel von Fersen at some point, there is no evidence of an extramarital affair, and to over-speculate on the Queen's personal feelings is to violate the sanctuary of the human heart. Whatever her sentiments, they did not interfere with her duties as wife, mother, and queen. Adultery for a queen of France was high treason and if any of her many enemies at court discovered such a situation, had it existed, Louis XVI would have been forced to take her children away from her and banish her to a convent. Even the most basic knowledge of her temperament suggests that she was devoted to her children and would never have risked being separated from them. What people need to understand is that the Queen stood in the way of those who wanted to destroy the Altar and the Throne in France, so every aspect of her life, every relationship, her friendships, her marriage, her motherhood, were smeared by those who wished to destroy her reputation and her influence. Marie-Antoinette stood in the way of the triumph of the Revolution and so she had to be obliterated. Fersen was scrupulous in excising anything in his correspondence with her that might be in the least compromising. But many of the redacted lines of the Queen's letters, those which are in her own hand, have been found to be of the same ink as the originals and therefore scribbled out by herself, as people often had to do when writing by hand and without whiteout.

In her determination to save the lives of her family, restore the royal authority, and preserve the throne for her son, Marie-Antoinette wrote hundreds of letters, not only to Count Fersen, but to her relatives in Austria and Italy, to Comte Mercy the Austrian ambassador, to the Vatican, to fellow monarchs such as the Queens of Spain and Portugal, and to moderate revolutionaries such as Barnave. One must remember that from any careful study of her correspondence it appears that the Queen was balancing precipitously between opposing parties as she attempted to manipulate Fersen, Barnave, and Mercy into doing what she needed them to do. Apparently there are huge portions of the Queen's correspondence missing and so people tend to fill in the gaps with romance. They forget that the first person on her mind was not Axel von Fersen but the Dauphin Louis-Charles and saving the throne for him.

Many of the letters were written in cipher, that is, in a secret code, which could be broken only by using certain key words. The complexity of the ciphers should destroy forever the myth that Marie-Antoinette was not intelligent; indeed, she must have been clever in order to adroitly master so many puzzles. Writing in code could be challenging. As Marie Antoinette wrote to the Comte de Provence: "At length I have succeeded in deciphering your letter, my dear Brother, but it was not without difficulty. There were so many mistakes [in the use of the cipher]. Still, it is not surprising, seeing that you are a beginner and that your letter was a long one...." (O. G. Heidenstam, ed. The Letters of Marie Antoinette, Fersen and Barnave, 1926, p.51, reprint at Google) Sometimes white or invisible ink was also used, about which the Queen complained, saying: "Little accustomed to writing in this manner, my writing will be indecipherable." (Marie-Antoinette to Mercy, 14 May 1791, Feuillet de Conches1, Vol.2, p.54)

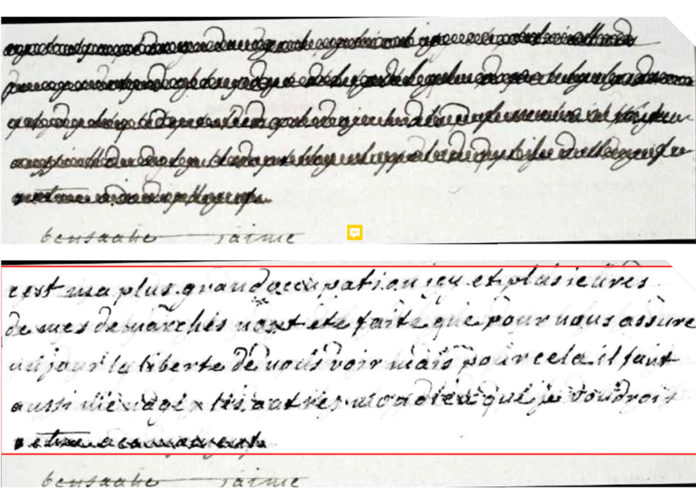

The Queen burned most of the letters she received but many of those she sent to others have been preserved. The relatives of Axel von Fersen saved some original manuscripts of the letters from the Queen to Fersen, although not always in her hand-writing but in Fersen's after he had decoded it. Below is a letter of October 19, 1791 in the Queen's hand with parts scribbled out by Fersen. Newly deciphered, in English it roughly says: "It is my biggest occupation here and several endeavors have been made only to ensure the freedom to see us but for that it is also necessary to spare the others my God I wish I was right now." It is impossible to discern exactly what she means without the context of the entire letter, which I hope will be available when the researchers publish their book. One can only guess that it has to do with the conditions at the Tuileries where the Royal Family, and especially the Queen, were constantly watched by guards.

The words are those of a woman in danger writing to the only person capable of rescuing her and her family, as he had done before but failed. As Isabelle Aristide-Hastir, archivist-paleographer, general curator of heritage at the National Archives, has commented:

You see, we are not at all in erotic vocabulary. Not at all. It is not simply because they are in different social conditions, she is the queen and he is a Swedish count, because we can see from their letters, even if there is a lot of respect one towards the other, that they are extremely united in thoughts, that is to say that they exchange in a very fluid way and even if they use the vocabulary of the time, of the 18th century, which is all quite charming, there is no stiffness in their correspondence. (Translated by Tea at Trianon.)It must be remembered that Marie-Antoinette had a passionate and exaggerated manner of writing to all of her friends and family. To her friend Madame de Polignac her words were as loving as any to Fersen, calling her "mon cher coeur" that is "my dear heart" and saying such things as "je vous embrasse très fort" which means "I kiss you hard." Such was her manner of expression with those of whom she was fond. It must also be kept in mind that Marie-Antoinette absolutely needed the help for the royal cause that only Fersen could give in the outside world; it should not be surprising if her words to him were especially tender. As a friend wrote to me: "It is the vocabulary of devotion, not of eroticism....as if they were heroes of chivalry...To me, it is the proof they never were actual lovers." I agree.

It should perhaps be pointed out that around the same time as Fersen was writing to the Queen he was having a passionate affair with an Italian lady named Eleonore Sullivan. Madame Sullivan was married to an Irishman but as of 1790 was the mistress of a Scotsman named Quintin Crawford. She was kept by Monsieur Crawford in an elegant house in Paris, where she had a hideaway for Fersen in the attic. It should also be remembered that after the deaths of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, Fersen wrote to their orphaned daughter Marie-Thérèse Charlotte of France asking for recompense of the money spent on the aborted escape attempt in June 1791. Chivalry obviously had its limits as far as Fersen was concerned.

Share

No comments:

Post a Comment