| Marie-Thérèse Charlotte de France around 1815 |

|

| Madame Royale after her release from prison |

|

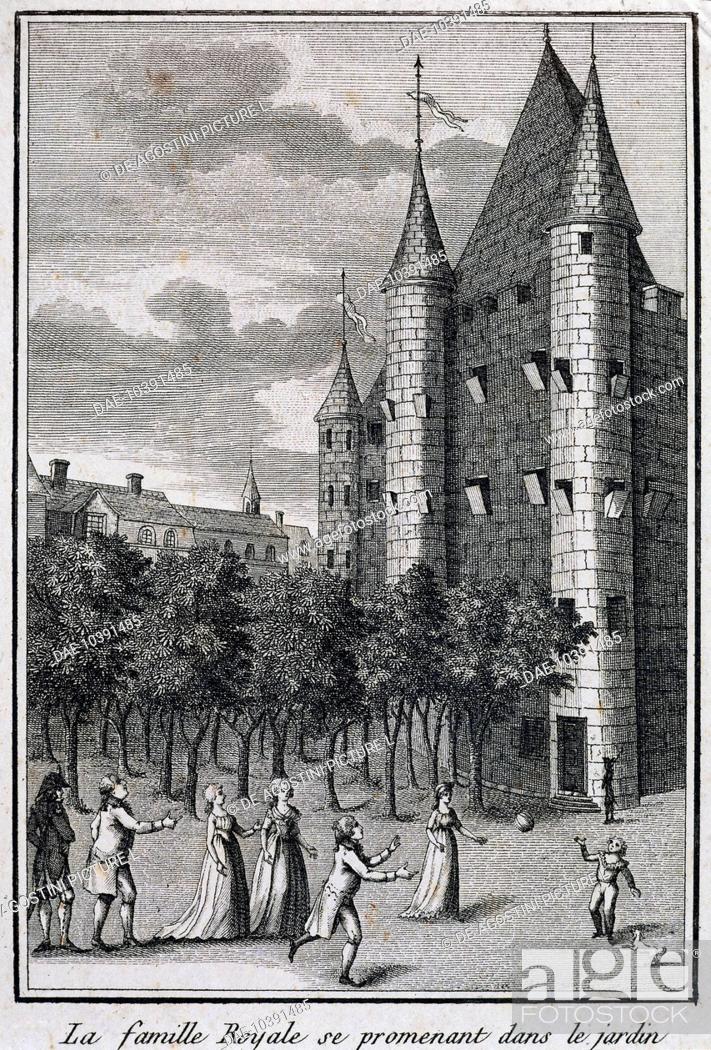

| The French Royal Family incarcerated at the Temple |

Like her father, mother, aunt, and brother, Marie-Thérèse was imprisoned in August of 1792 at the Temple, which had been built by the Knights Templar in the twelfth century and started out as fort. New headquarters emerged in the thirteenth century in the form of a fortress called enclos du Temple. The Temple originally contained buildings necessary for the order to function and included two towers: a massive one known as the Gross Tour (great tower) and a small one called Tour de Tour de César (Caesar’s Tower).

The great tower was where the royal family was imprisoned. It was 150 feet high with walls that were 9 feet thick. It consisted of four stories, all vaulted, and the interior was between 34 and 36 feet square. The second floor was reserved for the King and the third floor for the Queen. Both floors had an antechamber preceded by two doors, one of oak and the other of iron.

The King and the Dauphin (Louis-Charles) were housed together on the second floor and Marie-Thérèse, her mother, and her aunt (Madame Élisabeth) were placed on the third floor. The chamber that housed Marie-Thérèse and her mother was directly above the King’s chamber, and in it there was the Queen’s bed, a mahogany chest of drawer, and a wooden screen. There was also Marie-Thérèse’s bed that had three mattresses, a hair palliass, bolster, and two cotton quilts. In addition, the room had yellow paper on the walls.

During the royal family’s imprisonment, they were constantly insulted. Marie-Thérèse wrote that “My father was no longer treated as King. He was not called ‘Sire’ or ‘Your Majesty,’ but ‘Monsieur’ or ‘Louis.’”[1] Moreover, jailers were always sitting in his room, and one jailer purposely tried to torment him by singing a popular song of revolutionaries, known as “Le Carmagnole,” or smoking a pipe, something the King detested.

The royal family was unhappy while imprisoned at the Temple partly because news was hard to come by, and they only learned of the outside world by bits and pieces. How they knew something was afoot was if they heard the beating of the drums, but even then they did not know exactly what the drums meant.

The royal family’s unhappiness increased when Louis XVI was guillotined in January of 1793. Shortly after his execution, her brother Louis-Charles (Louis XVII) was removed on 3 July 1793 and housed in a different part of the Temple. After his removal Marie Antoinette never saw him again and his sister only saw him a couple of times. Life in the Temple was difficult, and it became more difficult when a few weeks after her brother’s separation, on the night of 1 August, at 1:00 in the morning, guards came and took her mother away. She supposedly threw her arms around her mother and had to be torn from her.

When the Queen left the Temple, she did not stoop low enough and hit her head on the lintel of door as she exited. One of her guards asked if she was hurt. She is reported to have said, “No, … nothing can hurt me now.”[2] She was then transferred from the Temple to an isolated cell in the Conciergerie, a prison that was the main penitentiary of a network of prisons throughout Paris and housed more than 2,700 people, who were summarily executed by guillotine.

The Queen arrived there at 3am and was known thereafter as “Prisoner n° 280.” She was placed in cell below courtyard level that was unpleasant and damp: The brick floor was thick with slimy mud and the walls were usually wet as water trickled down them because of the cell’s proximity to the Seine. Moreover, when the river was low and the walls dried out, she could see the appearance of pieces of old fleur-de-lis wallpaper.

After her mother’s removal from the Temple, Marie-Thérèse scratched her unhappiness onto a wall in her room. It read:

“Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte is the most unfortunate person in the world. She cannot hear news of her mother, not even to be reunited to her even though she has asked for it a thousand times. Long live my good mother whom I like and whose news I cannot know.”*[3]Marie Antoinette’s trial began on 14 October. It lasted 15 hours, and the next session that began on 15 October lasted 24 hours. The verdict probably came as no surprise to anyone. The sentence of death by guillotine was passed at 4:30am on the 16th, and when it was pronounced, Marie Antoinette didn’t say a single word. A few hours later, she was executed at the Place de la Concorde. Her death was followed by the death of her sister-in-law and Marie-Thérèse’s aunt, Madame Élisabeth, who was guillotined on 10 May 1794. (Read more.)

Share

1 comment:

Marie-Antoinette's last days at the Tuileries: http://www.nobility.org/2019/04/04/the-last-days-at-the-tuileries/

Post a Comment