Many Catholics, particularly priests, monks and nuns, were murdered by the revolutionary government for refusing to renounce the papal sovereignty. From World History:

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a deistic cult established by Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794) during the French Revolution (1789-1799). Its purpose was to replace Roman Catholicism as the state religion of France and to undermine the atheistic Cult of Reason which had recently gained popularity. It represented the peak of Robespierre's power and went unsupported after his downfall.

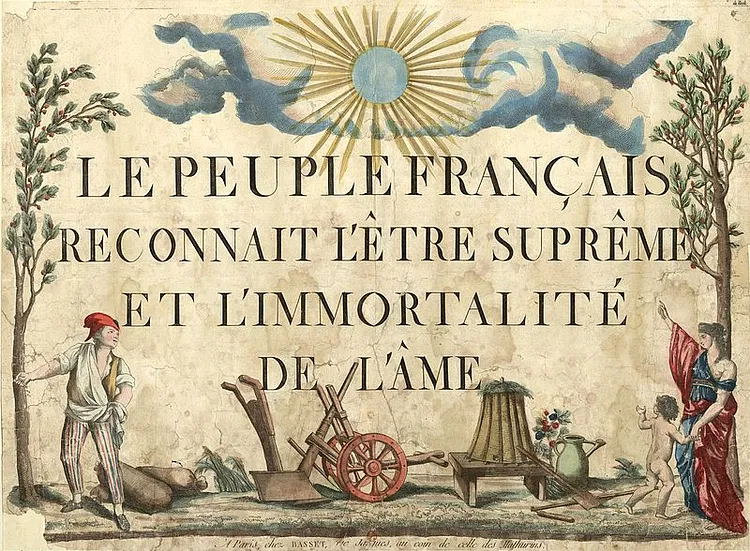

In establishing the Cult of the Supreme Being, Robespierre intended to shepherd the French Republic toward a state of absolute virtue, or moral excellence. He meant to use the idea of an abstract godhead, or Supreme Being, to educate the French people on the relationship between virtue and republican government, thereby creating a perfectly just society. According to the decree of 18 Floréal (7 May), the cult acknowledged the existence of a Supreme Being as well as the immortality of the human soul. Worship of the Supreme Being was to be done through acts of civic duty.

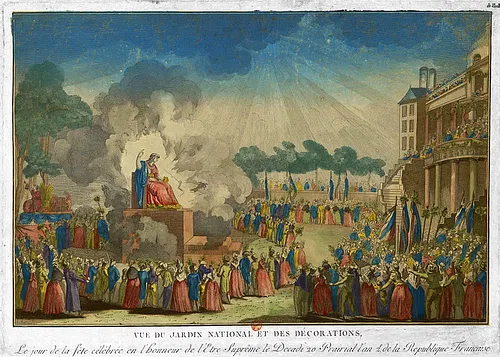

On 8 June 1794, a Festival of the Supreme Being was held on the Champ de Mars. Robespierre, who was then at the apex of his dictatorial powers, took on a central role in the festivities, giving him the appearance of pontiff to the new religion. It is thought that distaste for the cult, and for Robespierre's central position in it, helped lead to his downfall a little over a month later. According to historian Mona Ozouf, the Festival represented a certain revolutionary stiffness that foreshadowed the "sclerosis of the Revolution" (Ozouf, 24).

The French Revolution had been at odds with the Catholic Church since its beginning. A fundamental pillar of the oppressive Ancien Régime, the institution of the Church seemed to stand for corruption, superstition, and backwardness, all contrary to revolutionary values. In November 1789, Church lands were seized and nationalized to bolster France's withering economy, while the Civil Constitution of the Clergy forced all practicing clergymen to swear oaths to the new constitution and pledge that their loyalty to the French state would supersede their loyalty to the Pope in Rome.

Yet in this early phase of the Revolution, it was the institution of the church that was under attack rather than Christianity itself. Many citizens would still consider themselves Catholic, and many even sought to reconcile the Gallican Church with the Revolution; most early revolutionary festivals included sermons from constitutional priests, who made sure to draw parallels between revolutionary values and the Gospels and to refer to Jesus Christ as the ideal sans-culotte. Infants would be baptized with a tri-color cockade pinned to their diapers, being simultaneously given over to both Christ and the fatherland.

But before long, the differences between the Church and the Revolution became too vast to ignore. The Pope condemned the Revolution and excommunicated certain clergymen who had supported the new constitution. King Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792), after his failed flight to Varennes, made clear his disgust at the Revolution's treatment of the Church, further helping to associate it with corrupt aristocracy. In late 1791, the French Legislative Assembly declared that all clergymen who had not yet sworn oaths to the constitution were guilty of conspiracy and sentenced to deportation. The Assembly also legalized divorce and declared that all records of births, deaths, and marriages would henceforth be handled by secular officials only, removing an important function from the Church. (Read more.)

Share

No comments:

Post a Comment