Composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, an avid collector of Pre-Raphaelite art, remarked in a documentary some years ago that for his parents’ generation, there was no better way to reduce a polite English dinner party to sputtering contempt than mentioning these artists—they were ranked with Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals in their perceived lowbrow vulgarity. At the time of the 2012 Tate retrospective, a Guardian reviewer, talking to a collector of Victorian art, one of whose works had been borrowed for the exhibition, poked at the sore spot a bit, pointing out that Victorian art hasn’t always been fashionable. The collector’s response was telling: “Yes. But when people say they hate Victorian art, you have to ask: what is it they’re hating? They’re hating themselves, because they’re hating the stuff of which we’re made. Most middle-class people in Britain still live in Victorian houses. [The Victorians] gave us all sorts of things we take for granted.” Indeed.

One wonders whether the Pre-Raphaelite movement came to be considered vulgar not because of its tendency toward the maudlin, but because it didn’t go where the arc of history supposedly dictates. The Pre-Raphaelites’ real crime may be that they were quintessentially British. Going their own eccentric way, they forged a parallel artistic path that had only a passing relationship to, say, the deliberately brutal realism going on in France.

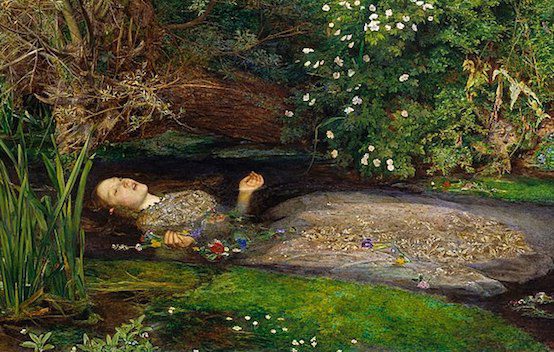

While Courbet was detailing female pudenda in his The Origin of the World in the 1860s, Hunt was painting one of the more moving works in the San Francisco exhibition, The Birthday, a portrait of his wife in which he lavishes palpable adoration on individual strands of her hair and on details of her dress and shawl. By 1888, Van Gogh and Gauguin were already long past Impressionism and hard at Post-Impressionism, but Pre-Raphaelite art only kept becoming more of what it already was—realistic, symbolic, spiritual, romantic, and medieval, as brilliantly summed up that year in John William Waterhouse’s exquisite The Lady of Shalott, depicting the penultimate scene in Tennyson’s poem in which the lady voyages alone, singing, down the river to Camelot.

From Sartle:

The term “Pre-Raphaelite” is really a misnomer, because Raphael and post-Raphael artists could be found on the PRB’s list of immortals (along with people like Homer, Jesus, Oliver Cromwell, and Tennyson! A motley crew). Artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti really came to admire late Venetian artists like Paolo Veronese as he moved away from earlier Pre-Raphaelite precepts and toward a version of painting concerned with aesthetics above all else. His richly wrought and glittering close-ups of women can be seen as spearheading the “Art for Art’s sake” movement. Inspiration for these sumptuous fabrics, luscious locks, and vague sense of morality can be seen in the works of late Italian masters. (Read more.)Share

No comments:

Post a Comment