ShareFor most Parisians, a stroll through the ruins of the Bastille in the summer of 1789 was the ultimate exercise in free will: the chance to personally trample over the regime’s most notorious symbol of oppression. Yet for Madame Tussaud—then the 27-year-old protégée of famed waxmaker Philippe Curtius—the experience was drenched in destiny.

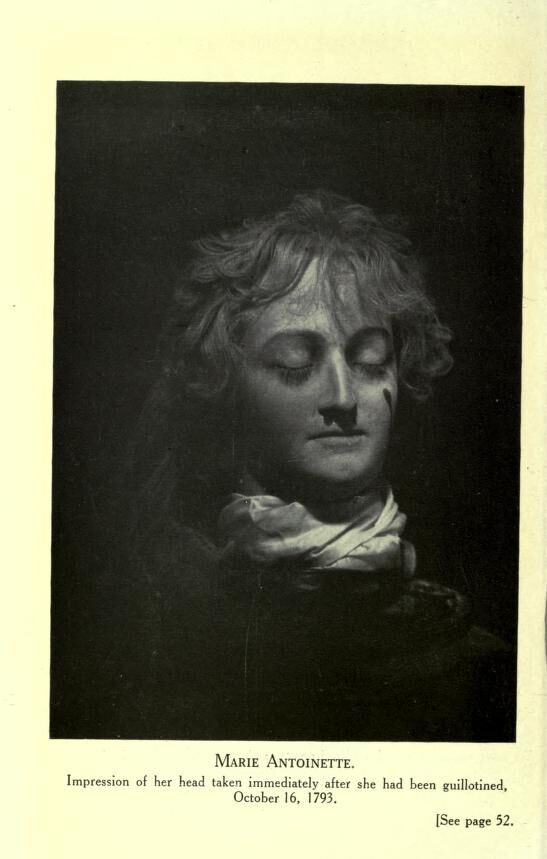

“Whilst descending the narrow stairs, her foot slipped,” recounts her earliest and most breathless biographer, “when she was saved by [Maximilien] Robespierre.” As it turned out, this would rank among her more pleasant encounters with the firebrand. “How little did Madame Tussaud then think,” the passage continues, “that she should, in a few years after, have his severed head in her lap in order to take a cast from it after his execution.”

Like Tussaud’s apocryphal tour of the Bastille, it is nearly impossible to separate the French waxmaker’s life and lore. A baptismal record places her birth in Strasbourg, France, on December 7, 1761. In a grisly portent of Tussaud’s future associations, her absent father came from a long line of public executioners dating back to the 15th century. Her mother was a housekeeper for Curtius—then a resident of Berne, Switzerland, and a doctor by training—fueling suspicion among scholars that Curtius and Tussaud’s mother may have been siblings or secret lovers.

Whether he was Tussaud’s uncle, father, or simply a benevolent physician, Curtius soon assumed the role of her guardian and artistic mentor. After impressing the visiting Prince de Conti, a cousin of Louis XV, with a small museum of anatomical wax miniatures produced as part of his medical practice, he accepted patronage to pursue wax modeling as his primary vocation in Paris. Tussaud and her mother joined him shortly thereafter. (Read more.)

Tuesday, March 13, 2018

More on Madame Tussaud

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment