USA Today columnist Kirsten Powers stated the liberal position with appropriate levels of self-righteousness: "Dear white people who are upset that you can't dress up as another race or culture for Halloween: your feelings don't matter. The only feelings that matter are of those who feel disrespected/mocked by you appropriating their culture for entertainment. Show some common decency."Share

No intelligent statement has ever begun with "Dear white people," and this was no exception. She says that only the feelings of the Offended Party matter. If a person feels that their culture is being "appropriated," then it is. This seems to be the consensus view among liberals. In an editorial published by the Cincinnati Enquirer, a white woman confessed to dressing her daughter as Pocahontas a few years ago. She says that she didn't intend to be racist, but she was racist. This is all quite mad for many reasons, but I'd like to highlight just one:

St. Patrick's Day.

My ancestors are Irish. On St. Patrick's Day, a whole lot of non-Irish people dress like Leprechauns and chug beer. If I were to adopt the language of the Left, I might say that my Irish heritage is appropriated, mocked, and reduced to crude stereotypes. But I will not say that. And I don't think that any of the real Irish people in Ireland say that, either. I think they just laugh at us and roll their eyes. As for me, I go to a bar and join the festivities. (Read more.)

Wednesday, October 31, 2018

Cultural Sensitivity

More Witches Than Presbyterians

The population of self-identified witches has risen dramatically in the United States in recent decades, as interest in astrology and witchcraft practices have become increasingly mainstreamed. While data is sparse, Quartz noted, the practice of witchcraft has grown significantly in recent decades; those who identify as witches has risen concurrently with the rise of the "witch aesthetic."Share

"While the U.S. government doesn't regularly collect detailed religious data, because of concerns that it may violate the separation of church and state, several organizations have tried to fill the data gap," Quartz reported.

"From 1990 to 2008, Trinity College in Connecticut ran three large, detailed religion surveys. Those have shown that Wicca grew tremendously over this period. From an estimated 8,000 Wiccans in 1990, they found there were about 340,000 practitioners in 2008. They also estimated there were around 340,000 Pagans in 2008."

Pew Research Center studied the issue in 2014, discovering that 0.4 percent of Americans, approximately 1 to 1.5 million people, identify as Wicca or Pagan, meaning their communities continue to experience significant growth. The rapid rise is not a surprise to some given philosophical and spiritual trends in culture.

"It makes sense that witchcraft and the occult would rise as society becomes increasingly postmodern. The rejection of Christianity has left a void that people, as inherently spiritual beings, will seek to fill," said author Julie Roys, formerly of Moody Radio, in comments emailed to The Christian Post Tuesday. "Plus, Wicca has effectively repackaged witchcraft for millennial consumption. No longer is witchcraft and paganism satanic and demonic," she said, "it's a 'pre-Christian tradition' that promotes 'free thought' and 'understanding of earth and nature.'" Yet such repackaging is deceptive, Roys added, "but one that a generation with little or no biblical understanding is prone to accept."

"It's tragic, and a reminder of how badly we need spiritual revival in this country, and also that 'our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the powers of this dark world,'" she said, referencing Ephesians 6, which explains spiritual warfare. (Read more.)

Tuesday, October 30, 2018

Entertaining Secrets

From Victoria:

Tucked away in the Great Smoky Mountains, author and interior designer Kathryn Greeley’s Chestnut Cottage reflects her philosophy that the best spaces are not decorated but collected. The cozy retreat, her home for more than three decades, often plays host to festive gatherings, from intimate dinners for four set before a blazing hearth to wine tastings and community events held in the property’s lovingly tended gardens. “Let your style be reflected in your entertaining,” Kathryn says. The seasoned hostess offers encouragement for welcoming guests with ease and confidence. Five years ago, I decided to act on my heart’s desire to write a book on entertaining and tabletop collections. In my interior design career, I have often been asked by clients to assist with their events. I love to cook and have always enjoyed doing floral arrangements—particularly using blossoms from our garden. My goal in writing this book was to inspire others to start collections, or use existing collections to design events for family and friends. (Read more.)Share

Like Nazis

Actor and conservative commentator Ben Stein said Saturday that the protesters who berated Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell at a Louisville restaurant the night before are “becoming like the brownshirts in the early days of the Nazi Party.” Mr. McConnell and his wife, Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao, were confronted at the Havana Rumba restaurant by at least two hecklers who reportedly stole the couple’s leftover food off their table and threw it outside. It was one of many similar incidents involving Republican politicians being heckled in public in recent months. Mr. McConnell was recently heckled by protesters at Reagan National Airport near Washington. Mr. Stein, a lawyer and economist who is also Jewish, told TMZ at Politicon in Los Angeles that leftist protesters are wading into fascistic territory. “Disgusting mob rule,” he said. “Antifa is becoming like the brownshirts in the early days of the Nazi Party. Very, very disgusting, shocking behavior — stunningly horrible." (Read more.)From The American Spectator:

I know my share about how the powers of darkness can attack a movie that does not hew to the PC Line. They did it to our movie, EXPELLED. We questioned why it was not allowed to even mention that there are questions about whether evolution answers all questions about the origins of life. We asked why teachers could not even mention that there are alternative theories about why and how life started and expanded.

Your humble servant in particular asked how it was possible that physical laws like gravity or thermodynamics could have just “evolved.” Didn’t there have to be some starting point for these laws which govern the universe? Who created these laws? Who enforces them? These questions were suggested to me by the smartest person I have ever met, Al Burton. And where is the evidence that one species evolves into another — not a variant of one species, but a whole different species?

I was attacked savagely by the powers that be. We delved into the connection of Hitler with Darwin, about how we explain why a theory that says there are superior and inferior races and that the inferior races should not be allowed to eat up all the food of the superior races is NOT connected with The Final Solution. We went to Nazi killing centers like Hadamar and Dachau and had the curators there tell us that what went on at these killing centers was not political. It was Darwinian.

I know I’m going to get slammed for saying these things. I’m prepared. But our movie’s run was cut short by a lawsuit by Yoko Ono of all people. Let’s support the Gosnell movie wherever and however we can. Abortion is the world’s leading monstrosity. It is its own form of genocide in which the people with political power use it to kill the people they do not respect — or who are a major inconvenience to them. Please support “The Gosnell Movie.” (Read more.)

From Ben Shapiro, on the murders in Pittsburgh:

On Saturday, in a constantly-repeating story as old as the Jewish people, a Jew-hating murderer decided to slaughter as many Jews as possible. This murderer shouted the slogan of Jew-haters throughout time: “All Jews must die.” That slogan has served to justify slaughter in the name of nationalism, in the name of communism, in the name of Christianity, in the name of Islam. Indeed, Jew-hatred is unique because Jew-hatred is infinitely chameleonic.Share

The Jews, however, are not.

Traditional Jewish thought suggests that every Jewish soul was present at the foot of Mount Sinai when God spoke to the nation of Israel, born and unborn. The Jews were bound in an inextricable covenant; we all consented, and we all became part of that covenant.

While the history of the Jewish people is filled with fractious division, the evidence suggests that this basic principle was fundamentally true – and history has treated the Jews as a closely-bound unit. Jewish identity wasn’t a choice. It was a reality.

Modernity has obscured this basic truth for many Jews. The enlightenment allowed Jews to believe they could exit the Jewish lineage, to abandon the faith of their fathers; freedom of choice came with freedom to exit. But the world is not that malleable. Jews, for better or worse, remain Jews. Every Jew knows this in his or her marrow. When we meet another Jew, the first thing we do is play Jewish geography: who knows whom, who is related to whom. That’s the rich side of being part of a global tribe – everyone is one degree removed from everyone else.

We’re reminded of that in joy, and we’re reminded of that in horror. (Read more.)

When Your Child is a Psychopath

Pychopaths have always been with us. Indeed, certain psychopathic traits have survived because they’re useful in small doses: the cool dispassion of a surgeon, the tunnel vision of an Olympic athlete, the ambitious narcissism of many a politician. But when these attributes exist in the wrong combination or in extreme forms, they can produce a dangerously antisocial individual, or even a cold-blooded killer. Only in the past quarter century have researchers zeroed in on the early signs that indicate a child could be the next Ted Bundy.Share

Researchers shy away from calling children psychopaths; the term carries too much stigma, and too much determinism. They prefer to describe children like Samantha as having “callous and unemotional traits,” shorthand for a cluster of characteristics and behaviors, including a lack of empathy, remorse, or guilt; shallow emotions; aggression and even cruelty; and a seeming indifference to punishment. Callous and unemotional children have no trouble hurting others to get what they want. If they do seem caring or empathetic, they’re probably trying to manipulate you.

Researchers believe that nearly 1 percent of children exhibit these traits, about as many as have autism or bipolar disorder. Until recently, the condition was seldom mentioned. Only in 2013 did the American Psychiatric Association include callous and unemotional traits in its diagnostic manual, DSM-5. The condition can go unnoticed because many children with these traits—who can be charming and smart enough to mimic social cues—are able to mask them.

More than 50 studies have found that kids with callous and unemotional traits are more likely than other kids (three times more likely, in one study) to become criminals or display aggressive, psychopathic traits later in life. And while adult psychopaths constitute only a tiny fraction of the general population, studies suggest that they commit half of all violent crimes. Ignore the problem, says Adrian Raine, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania, “and it could be argued we have blood on our hands.”

Researchers believe that two paths can lead to psychopathy: one dominated by nature, the other by nurture. For some children, their environment—growing up in poverty, living with abusive parents, fending for themselves in dangerous neighborhoods—can turn them violent and coldhearted. These kids aren’t born callous and unemotional; many experts suggest that if they’re given a reprieve from their environment, they can be pulled back from psychopathy’s edge. (Read more.)

Monday, October 29, 2018

Hunt Country

Not far from our nation’s capital, traffic-packed streets narrow to country lanes and polo ponies become more readily spotted than cars. Welcome to Middleburg, Virginia, a small town shaped by history, horses, viticulture, and enduring hospitality. The original stone fireplace, dating to 1728, has pride of place in The Red Fox Inn & Tavern. Its blazing fires have warmed many notable figures through the years, from Civil War generals to presidential hopefuls. An assemblage of American and European furniture mingles with a silver tea service and antique rugs at the Middleburg Antique Emporium. Dinnerware collectors will find a wonderful array, from Minton and Wedgwood china to Roseville pottery and majolica. (Read more.)Share

Why Are American Children Turning Violent?

Over the past 50 years, America has seen its youth assaulted by broken households, drugs, alcohol abuse, promiscuity, explicit music, violent movies and games. The traditional family of a father and mother raising their child has been undermined by a culture which questions authority and preaches the intolerance of tolerance. At public and charter schools, secular humanism has become a state sanctioned religion while Christianity, its precepts and moral virtues, are excluded from sight. In 1962, SCOTUS ruled school prayer was unconstitutional. In 1963, they removed the Bible. In 1966, the first mass shooting took place in Austin, TX. Coincidence? Since the 60s, debates over the public display of religious moral codes, such as the Ten Commandments, have permeated court decisions.

In 2004, counties in Kentucky were forced to remove their Ten Commandments displays from public schools, while in 2017 a Pennsylvania school district remove a Ten Commandments monument erected at a public high school because one person objected. Removing our Judeo-Christian heritage thereby removes the foundation of our mores as a society. Moreover, the lessons of responsibility and accountability are hardly ever taught. Respect is taught first at home. However, in many urban settings, parents are either unwilling or unable to raise their children to function correctly in social settings.

It is a problem that is systemic. When I inquire from admins as to a troubled student’s home life, over 50% of the time administration responds the student in question has only one parent. Sadly, it is not uncommon for drugs, mental, and physical abuse to be a part of the student’s home life. I have witnessed firsthand children dropped off at 6AM and picked up after 6PM by parents who do not even have jobs. What do their kids spend their non-class time doing? Watching adult sitcoms, violent movies, playing mature rated video games, and engaged on social media — just like Nicolas Cruz.

This exposure to confrontational and violent programing spills over into the classroom which is often the first place where children learn social functioning skills apart from their households. More and more, teachers are forced to tolerate classroom profanity, disrespect towards authority, disregard of rules, and lewd side conversations by adolescents who are being raised by YouTube and social media. With no religious values being instilled, a dearth of accountability and family structure, and an immoral and violent culture being presented to our children 24/7 as the “norm”, should it be any surprise that school shootings are on the rise? There has been a terrific moral decline in American society over the last fifty years. If you remove God and moral values, deal with the consequences of a godless and immoral generation. (Read more.)Share

Public Schools in Jane Austen’s Day

Public schools were public in the sense that boys were taught in groups outside of their private homes, not in the sense that these institutions were funded by public funds. A number of public schools existed, but the landed elite in particular chose to send their sons to a select number of these schools: Eton, Harrow, Winchester, Westminster, Rugby, Charterhouse and Shrewsbury. (Adkins, 2013) The exact timing and duration of a boys stay at school varied greatly. Some were sent as young as age seven and stayed until age eighteen. More commonly boys started public schools around age thirteen and stayed about five years. Though Regency era education was very different from modern education, two factors in particular seem to distinguish it most from modern schooling: the curriculum taught and the lifestyle of the students.

In his 1693 treatise, Some Thoughts Concerning Education, John Locke recommended that instruction in foreign language (beginning with a living language like French) should start as soon as a boy could speak English. Locke considered Latin and Greek to be absolutely essential to a gentleman’s education, enabling him to read classical literature. In addition, he endorsed the study of geography, astronomy, anatomy, chronology, history, mathematics and geometry. (Morris, 2015).

Based on Locke’s foundations, students were expected to know some Latin upon arrival to public school. “The first two years of their education was entirely a study of Latin–memorizing, reciting, reading, and answering set questions in that language, so pronunciation too. … Thus they learned to be confident public speakers, first in Latin, then in classical Greek and finally in English.” (Bennetts 2010) These studies also developed an understanding of the moral and philosophical issues brought up by the classical thinkers and a literary appreciation of poetry and prose. Dancing, fencing and other sports also featured in some curriculums.Share

What was notably absent from both public school and university educations were courses on anything the modern mind would consider practical. Since these establishments catered to gentlemen who were not destined to actually work for their living, courses like bookkeeping or land management that might equip them for jobs (oh the horror!) were relegated to schools that catered to the sons of men in trade. (Selwyn 2010) (Read more.)

Sunday, October 28, 2018

Quintessential Couture

From Victoria:

Stepping into the atelier of Catherine Walker & Co. in Bury Walk, a charming seven-studio mews in the Chelsea area of London, is like stumbling upon the secret cache of a couturier, one with exceptional taste. Cofounded in 1977 by Said Cyrus and his late wife, Catherine Walker, the business quickly caught the attention of women who were drawn to the clean lines and pure elegance of the couture designs. It is no surprise that these chic collections were favored by Princess Diana, who was known for her polished sense of style; she donned more than a thousand of the company’s creations over the years. The current Duchess of Cambridge is following in her late mother-in-law’s footsteps and is often seen in the firm’s designs, such as the stunning black velvet coat she wore for last fall’s Festival of Remembrance at Albert Hall. (Read more.)Share

The Real Reason They Hate Trump

Every big U.S. election is interesting, but the coming midterms are fascinating for a reason most commentators forget to mention: The Democrats have no issues. The economy is booming and America’s international position is strong. In foreign affairs, the U.S. has remembered in the nick of time what Machiavelli advised princes five centuries ago: Don’t seek to be loved, seek to be feared.The contrast with the Obama years must be painful for any honest leftist. For future generations, the Kavanaugh fight will stand as a marker of the Democratic Party’s intellectual bankruptcy, the flashing red light on the dashboard that says “Empty.” The left is beaten.

This has happened before, in the 1980s and ’90s and early 2000s, but then the financial crisis arrived to save liberalism from certain destruction. Today leftists pray that Robert Mueller will put on his Superman outfit and save them again.For now, though, the left’s only issue is “We hate Trump.” This is an instructive hatred, because what the left hates about Donald Trump is precisely what it hates about America. The implications are important, and painful.

Not that every leftist hates America. But the leftists I know do hate Mr. Trump’s vulgarity, his unwillingness to walk away from a fight, his bluntness, his certainty that America is exceptional, his mistrust of intellectuals, his love of simple ideas that work, and his refusal to believe that men and women are interchangeable. Worst of all, he has no ideology except getting the job done. His goals are to do the task before him, not be pushed around, and otherwise to enjoy life. In short, he is a typical American—except exaggerated, because he has no constraints to cramp his style except the ones he himself invents.

Mr. Trump lacks constraints because he is filthy rich and always has been and, unlike other rich men, he revels in wealth and feels no need to apologize—ever. He never learned to keep his real opinions to himself because he never had to. He never learned to be embarrassed that he is male, with ordinary male proclivities. Sometimes he has treated women disgracefully, for which Americans, left and right, are ashamed of him—as they are of JFK and Bill Clinton.

But my job as a voter is to choose the candidate who will do best for America. I am sorry about the coarseness of the unconstrained average American that Mr. Trump conveys. That coarseness is unpresidential and makes us look bad to other nations. On the other hand, many of his opponents worry too much about what other people think. I would love the esteem of France, Germany and Japan. But I don’t find myself losing sleep over it.

The difference between citizens who hate Mr. Trump and those who can live with him—whether they love or merely tolerate him—comes down to their views of the typical American: the farmer, factory hand, auto mechanic, machinist, teamster, shop owner, clerk, software engineer, infantryman, truck driver, housewife. The leftist intellectuals I know say they dislike such people insofar as they tend to be conservative Republicans.

Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama know their real sins. They know how appalling such people are, with their stupid guns and loathsome churches. They have no money or permanent grievances to make them interesting and no Twitter followers to speak of. They skip Davos every year and watch Fox News. Not even the very best has the dazzling brilliance of a Chuck Schumer, not to mention a Michelle Obama. In truth they are dumb as sheep. Mr. Trump reminds us who the average American really is. Not the average male American, or the average white American. We know for sure that, come 2020, intellectuals will be dumbfounded at the number of women and blacks who will vote for Mr. Trump. He might be realigning the political map: plain average Americans of every type vs. fancy ones.

Many left-wing intellectuals are counting on technology to do away with the jobs that sustain all those old-fashioned truck-driver-type people, but they are laughably wide of the mark. It is impossible to transport food and clothing, or hug your wife or girl or child, or sit silently with your best friend, over the internet. Perhaps that’s obvious, but to be an intellectual means nothing is obvious. Mr. Trump is no genius, but if you have mastered the obvious and add common sense, you are nine-tenths of the way home. (Scholarship is fine, but the typical modern intellectual cheapens his learning with politics, and is proud to vary his teaching with broken-down left-wing junk.) This all leads to an important question—one that will be dismissed indignantly today, but not by historians in the long run: Is it possible to hate Donald Trump but not the average American?

True, Mr. Trump is the unconstrained average citizen. Obviously you can hate some of his major characteristics—the infantile lack of self-control in his Twitter babble, his hitting back like a spiteful child bully—without hating the average American, who has no such tendencies. (Mr. Trump is improving in these two categories.) You might dislike the whole package. I wouldn’t choose him as a friend, nor would he choose me. But what I see on the left is often plain, unconditional hatred of which the hater—God forgive him—is proud. It’s discouraging, even disgusting. And it does mean, I believe, that the Trump-hater truly does hate the average American—male or female, black or white. Often he hates America, too. Granted, Mr. Trump is a parody of the average American, not the thing itself. To turn away is fair. But to hate him from your heart is revealing. Many Americas were ashamed when Ronald Reagan was elected. A movie actor? But the new direction he chose for America was a big success on balance, and Reagan turned into a great president. Evidently this country was intended to be run by amateurs after all—by plain citizens, not only lawyers and bureaucrats.Those who voted for Mr. Trump, and will vote for his candidates this November, worry about the nation, not its image. The president deserves our respect because Americans deserve it—not such fancy-pants extras as network commentators, socialist high-school teachers and eminent professors, but the basic human stuff that has made America great, and is making us greater all the time. (Read more.)

From Piers Morgan at The Daily Mail:

Given all the fire, brimstone and perpetual outrage about Trump since he won the White House, this is a truly remarkable state of affairs. Of course, America’s liberals will respond to the shock poll in the way they respond to all things Trump - with fury, incredulity and by sticking their collective heads in the sand. ‘HOW CAN THIS BE HAPPENING?’ they will wail, uncontrollably. ‘WHAT THE F**K IS WRONG WITH PEOPLE WHO LIKE HIM?’ they will howl into each other’s kale salads. ‘THIS IS THE END OF PLANET EARTH!’ they will sob, in their normal understated manner. All of which will be music to the ears of Trump, a man who absolutely revels in liberal hysteria because he knows it works for him, as this new poll proves. The more Trump-bashers scream abuse at and about him, the more it fires up his base – and indeed, the more it fires up Trump himself. (Read more.)Share

Gen Z: Get Ready to Adapt

About 17 million members of Generation Z are now adults and starting to enter the U.S. workforce, and employers haven’t seen a generation like this since the Great Depression. They came of age during recessions, financial crises, war, terror threats, school shootings and under the constant glare of technology and social media. The broad result is a scarred generation, cautious and hardened by economic and social turbulence.

Gen Z totals about 67 million, including those born roughly beginning in 1997 up until a few years ago. Its members are more eager to get rich than the past three generations but are less interested in owning their own businesses, according to surveys. As teenagers many postponed risk-taking rites of passage such as sex, drinking and getting driver’s licenses. Now they are eschewing student debt, having seen prior generations drive it to records, and trying to forge careers that can withstand economic crisis.

Early signs suggest Gen Z workers are more competitive and pragmatic, but also more anxious and reserved, than millennials, the generation of 72 million born from 1981 to 1996, according to executives, managers, generational consultants and multidecade studies of young people. Gen Zers are also the most racially diverse generation in American history: Almost half are a race other than non-Hispanic white.

With the generation of baby boomers retiring and unemployment at historic lows, Gen Z is filling immense gaps in the workforce. Employers, plagued by worker shortages, are trying to adapt. LinkedIn Corp. and Intuit Inc. have eased requirements that certain hires hold bachelor’s degrees to reach young adults who couldn’t afford college. At campus recruiting events, EY is raffling off computer tablets because competition for top talent is intense.

Companies are reworking training so it replicates YouTube-style videos that appeal to Gen Z workers reared on smartphones. “They learn new information much more quickly than their predecessors,” says Ray Blanchette, CEO of Ruby Tuesday Inc., which introduced phone videos to teach young workers to grill burgers and slow-cook ribs. Growing up immersed in mobile technology also means “it’s not natural or comfortable for them necessarily to interact one-on-one,” he says.

Demographers see parallels with the Silent Generation, a parsimonious batch born between 1928 and 1945 that carried the economic scars of the Great Depression and World War II into adulthood while reaping the rewards of a booming postwar economy in the 1950s and 1960s. Gen Z is setting out in the workplace at one of the most opportune times in decades, with an unemployment rate of 4%.

“They’re more like children of the 1930s, if children of the 1930s had learned to think, learn and communicate while attached to hand-held supercomputers,” says Bruce Tulgan, a management consultant at RainmakerThinking in Whitneyville, Conn.

At Ruby Tuesday, Mr. Blanchette can’t find enough young adult workers to wait tables and wash dishes because Uber and Lyft siphoned them off with worker-driven scheduling. “It’s a swipe one way on their phone and they’re working, and a swipe the other way and they’re not. It’s tough to compete against that,” he says.

Those who do pick Ruby Tuesday want assurances they will get health insurance and other benefits. “They’re not even going to access these benefits that we offer, because they’re staying on their parents plan, but they want to know it’s there,” Mr. Blanchette says. “They’re thinking, ‘What if I graduate college and I don’t find a job, and I need to stay here?’ ”

Gen Z’s attitudes about work reflect a craving for financial security. The share of college freshmen nationwide who prioritize becoming well off rose to around 82% when Gen Z began entering college a few years ago, according to the University of California, Los Angeles. That is the highest level since the school began surveying the subject in 1966. The lowest point was 36% in 1970. The oldest Gen Zers also are more interested in making work a central part of their lives and are more willing to work overtime than most millennials, according to the University of Michigan’s annual survey of teens.

“They have a stronger work ethic,” says Jean Twenge, a San Diego State University psychology professor whose book “iGen” analyzes the group. “They’re really scared that they’re not going to get the good job that everybody says they need to make it.”

Just 30% of 12th-graders wanted to be self-employed in 2016, according to the Michigan survey, which has measured teen attitudes and behaviors since the mid-1970s. That is a lower rate than baby boomers, Gen X, the group born between 1965 and 1980, and most millennials when they were high-school seniors. Gen Z’s name follows Gen X and Gen Y, an early moniker for the millennial generation.

College Works Painting, which hires about 1,600 college students a year to run small painting businesses across the country, is having difficulty hiring branch managers because few applicants have entrepreneurial skills, says Matt Stewart, the Irvine, Calif., company’s co-founder.

“Your risk is failure, and I do think people are more afraid of failure than they used to be,” he says. A few years ago Mr. Stewart noticed that Gen Z hires behaved differently than their predecessors. When the company launched a project to support branch managers, millennials excitedly teamed up and worked together. Gen Z workers wanted individual recognition and extra pay. The company introduced bonuses of up to $3,000 to encourage them to participate.Michael Solohubovskyy was 12 when his family left Ukraine in 2012 for Snohomish County, Wash. His father, a former taxi driver, instilled in him that hard work was key to success. Reading about billionaires Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos reinforced the message. After graduating from high school, Mr. Solohubovskyy, now 18, took a job at Boeing as an electrical technician. The company pays for his classes to earn an airframe and powerplant license. Once a month he also works at a Tommy Hilfiger store so he can get a 50% discount on clothing. “I never want to fail,” says Mr. Solohubovskyy. “When you read the stories about famous people, they have to sacrifice something to achieve. I’ll sacrifice my sleep.”

After seeing their millennial predecessors drown in student debt, Gen Z is trying to avoid that fate. The share of freshmen who used loans to pay for college peaked in 2009 at 53% and has declined almost every year since, falling to 47% in 2016, according to the UCLA survey.

Denise Villa, chief executive of the Center for Generational Kinetics in Austin, says focus groups show some Gen Z members are choosing less-expensive, lower-status colleges to lessen debt loads. Federal Reserve Bank of New York data show that nationwide, overall student loan balances have grown at an average annual rate of 6% in the past four years, down sharply from a 16% annual growth rate in the previous decade.

Lana Demelo, a 20-year-old in San Jose, Calif., saw her older sister take on debt when she became the first person in their family to attend college. “I just watched her go through all those pressures and I felt like me personally, I didn’t want to go through them,” says Ms. Demelo. She enrolled in Year Up, a work training program that places low-income high-school graduates in internships, got hired as a project coordinator at LinkedIn and attends De Anza College in Cupertino part-time....

Gen Z is reporting higher levels of anxiety and depression as teens and young adults than previous generations. About one in eight college freshmen felt depressed frequently in 2016, the highest level since UCLA began tracking it more than three decades ago.

That is one reason EY three years ago launched a program originally called “are u ok?”—now called “We Care”—a companywide mental health program that includes a hotline for struggling workers. Mr. Stewart, of College Works Painting, says he wasn’t aware of any depressed employees 15 years ago but now deals frequently with workers battling mental-health issues. He says he has two workers with bipolar disorder that the company wants to promote but can’t “because they’ll disappear for a week at a time on the down cycle.”

Smartphones may be partly to blame. Much of Gen Z’s socializing takes place via text messages and social media platforms—a shift that has eroded natural interactions and allowed bullying to play out in front of wider audiences. In the small town of Conneaut Lake, Penn., Corrina Del Greco and her friends joined Snapchat and Instagram in middle school. Ms. Del Greco, 19, checked them every hour and fended off requests for prurient photos from boys. She shut down her social media accounts after deciding they “had a little too much power over my self-esteem,” she said. That has helped her focus on studying at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Fla., to become a software engineer, a career she sees as recession-proof. When the last downturn hit, she remembers cutting back on gas and eating out because her parents’ music-lesson business softened. “I learned a lot about the value of money,” she says. “I’ve always wanted to have a very secure lifestyle, secure income.” She says the negative experience with social media made her want a professional LinkedIn page, and she took a seminar at college to learn how to do that.

The flip side of being digital natives is that Gen Z is even more adept with technology than millennials. Natasha Stough, Americas campus recruiting director at EY in Chicago, was wowed by a young hire who created a bot to answer questions on the company’s Facebook careers page. To lure more Gen Z workers, EY rolled out video technology that allows job candidates to record answers to interview questions and submit them electronically.

Share

Getting employees comfortable with face-to-face interactions takes work, Ms. Stough says. “We do have to coach our interns, ‘If you’re sitting five seats away from the client and they’re around the corner, go talk to them.’ ” Intense competition for Silicon Valley talent prompted Intuit to change its recruiting practices. The Mountain View, Calif., financial software maker began responding to all 4,500 young adults who apply for internships and first jobs annually regardless of whether they received offers. Not responding could hurt the company’s brand because tech-savvy young adults have the power to influence peers, says Nick Mailey, Intuit’s vice president of talent acquisition.Intuit moved job postings to Slack, a messaging platform, so workers who pay less attention to email don’t overlook opportunities inside the company. “They will gain a skill and move onto the next thing,” Mr. Mailey says. “You’re seeing more attrition.”

LinkedIn, which used to recruit from about a dozen colleges, broadened its efforts to include hundreds of schools and computer coding boot camps to capture a diverse applicant pool that mirrors the changing population. “We don’t care where they went to school or frankly if they went to school,” says Brendan Browne, the company’s vice president of global talent acquisition. “We’ll take talent and build them from scratch.”

Mr. McKeon, the Ohio student, sees a silver lining growing up during tumultuous times. He used money from his grandfather and jobs at McDonald’s and a house painting company to build a stock portfolio now worth about $5,000. He took school more seriously knowing that “the world’s gotten a lot more competitive.”

“With any hardship that people endure in life, they either get stronger or it paralyzes them,” Mr. McKeon says. “These hardships have offered a great opportunity for us to get stronger.” (Read more.)

Saturday, October 27, 2018

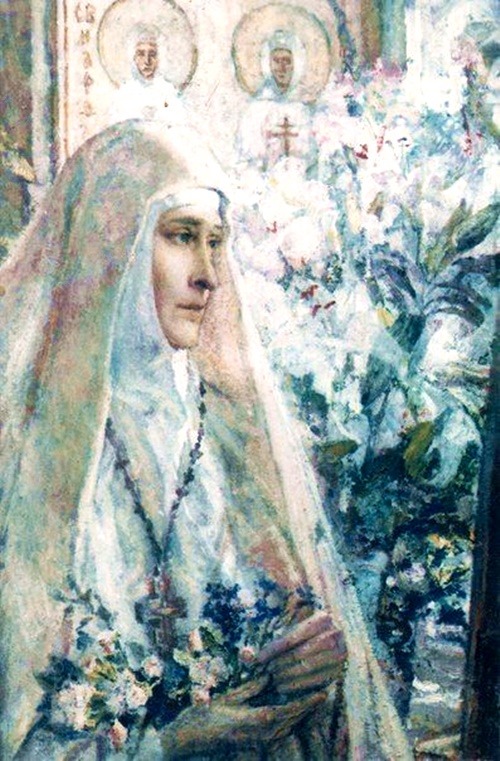

Life Principles of Grand Duchess Elizabeth

A film, HERE. Russian videos, HERE and HERE.Deeds and letters are those things that in the best possible way show what kind of person someone is. The letters of Grand Duchess Elizabeth reveal the principles which laid the foundation of her life and relationships with people around her. These letters help us understand the reasons why the high-society beauty became a saint in her lifetime. In Russia, Elizabeth Feodorovna was renowned not only as “Europe’s most beautiful princess”, a sister of the empress and wife of the tsar’s uncle. The country knew her as founder of the Martha and Mary Convent, a convent of a new type. In 1918 Elizabeth Fyodorovna was on Lenin’s order thrown to an abandoned mine, hidden in an impenetrable forest, so that no one could ever find her.In marrying Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, Elizabeth Fyodorovna was free to remain Lutheran, as she had been by birth. According to the rules of that time, conversion was only necessary for those who married heirs of the Russian throne. However, on the seventh year of marriage she decided to adopt the Orthodox faith. She made this step of her own volition, not for her husband.A portion from a letter to her father, Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and Rhine (January 1, 1891):(Read more.)I have come to this decision [to convert to the Orthodoxy] only due to my deep faith. I feel that I should stand before God with a pure and faithful heart. How easy it would for everything to remain as it is now, and how fake and hypocritical at the same time! How can I lie to everyone, pretend being a Protestant, and showing it by my appearance, while my soul has already embraced the Orthodox faith? After I’ve spent six years in this country and already “found” religion, I’ve been thinking, thinking long and hard, about everything. To my surprise, I almost fully understand texts and services in Slavonic, despite never learning the language. You say that I’m enchanted by the splendor of the churches. But I don’t think you’re right. I’m impressed neither by anything visual nor by the service itself, but the foundation of faith. Visual attributes remind me of the inner part of it.

|

| Elizabeth of Hesse, Grand Duchess of Russia |

|

| The Grand Duchess in a family theatrical about nuns |

|

| Marriage to Grand Duke Serge |

|

| As a nun |

|

| As a saint |

From Catholic Exchange, HERE. Share

Why Kids R Commies

ShareThe opinion polls agree…In a Pew Research Center study of Americans age 22-37, 57% called themselves “mostly” or “consistently” liberal. In a Gallup poll of Americans age 18-29, 51% had a positive view of socialism. And in a University of Chicago survey of Americans age 18-34, 44% said they would prefer to live in a socialist country. “Mostly” or “consistently” liberal may not be enough for young voters. Ten-term incumbent congressmen Michael Capuano (D-MA) and Joe Crowley (D-NY) are as mostly consistently liberal as they come. And they were kicked to the curb in Democratic primaries by leftist “progressives” Ayanna Pressley and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, respectively.What’s the matter with kids today?Nothing new. The brats, the squirts, the fuzz-faced mooncalves, the sap-green sweet young things, and the wet-behind-the-ears in general have always been “Punks for Progressives.” As soon as kids discover that the world isn’t nice, they want to make it nicer. And wouldn’t a world where everybody shares everything be nice? Aw… Kids are so tender-hearted.Kids are broke – so they want to make the world nicer with your money.But kids are broke – so they want to make the world nicer with your money. Kids don’t have much control over things – so they want to make the world nicer through your efforts. And kids are busy being young – so it’s your time that has to be spent making the world nicer…For them. (Read more.)

Labels:

Communism,

Humor,

Land of the Free,

Motherhood,

Politics,

The Revolution,

Work

Why Kids R Commies

The Rise of Candace Owens

ShareIt’s a Wednesday morning at Liberty University and the basketball arena is packed with nearly 10,000 people. Students reach their arms skyward, eyes closed, entranced in deafening Christian rock music. Backstage, administrators and students dote on Candace Owens, that day’s convocation speaker, who has quickly built a career trashing liberal politics with a millennial fierceness. She hasn’t rehearsed. It protects her authenticity. But she knows her beats.Onstage, she speaks for about 24 minutes, calmly gliding back and forth across the stage in heels, attacking some of her usual targets: Planned Parenthood, feminism, the welfare system. She builds to the moment. Then, she goes for it. “Kanye West. Man, he’s a wonderful man,” she says to applause and cheering — breaking the quiet of what had become a calm, attentive audience. “What is it that President Donald Trump, Kanye West and Candace Owens have in common?” she asks rhetorically. “Kanye West describes it as 'dragon energy' and to me I think it’s individualism. It’s believing in yourself. It’s standing up in the face of everybody telling you you can’t.” Owens embraces her role as the young black woman defending conservatism, attacking liberals and praising two of America's more complicated men. (Read more.)

Friday, October 26, 2018

Decorating with White

From Southern Lady:

“Playing with texture is the key to designing with white,” says Beverly, because the inherent lack of contrast in an all-white room makes working with this scheme difficult. Wispy drapes bring ease and femininity to crisp white marble tile in this stunning entryway by Cindy Barganier, creating contrasting surfaces that prevent the room from appearing flat. (Read more.)Share

Ethnic Play-acting

If a fraternity at a big state university had made the kind of mockery of Native Americans that Senator Warren has, it would be kicked off campus — and no pleas about a vague and mysterious “Cherokee princess” way back in the lost ages of the family history would save them. Senator Warren is the main offender of the moment, a significantly-whiter-than-the-average-white-woman white woman who has for years been masquerading as a Native American, telling transparent bumfodder stories about how her parents had to elope because her mother was part Cherokee and part Delaware, an obvious attempt to claim some of that victimhood juice secondhand. She allowed herself to be advertised as a woman of color by Harvard, happy in the coincidence that “her major professional advances — to the University of Pennsylvania and then to Harvard — came after she began formally identifying as Native American, a distant descendant of Cherokee and Delaware tribes,” as the Boston Globe put it. (Read more.)Share

All is Well…Keep the Joy

From Confessions of a Timeless Diva:

ShareTook a great deal of life to get us where we are dear Divas. Most of us have had our share of life’s ups and downs, with all the caring, nurturing, loving, raising, care taking and working that we’ve done. We deserve to be happy and enjoy the smallest or mega things we embark on. Happiness is a choice. Joy is a feeling that belongs to us. No one has the right to take that away from us. So- don’t let anyone.

Easier said than done- especially if you were rarely first on your list of priorities. Still. Make this a priority. Take the time, breathe and allow yourself. “All is well” This is my new motivating phrase. It’s my new liberating spot. We’re smart enough to know that things are not constant. Everything passes. So why not begin today by accepting your joy?

Today, if someone or something tries to steal your joy, don’t let yourself be dragged into the trap. Breathe and say to yourself: “All is well”. (Cause eventually, you know it will be). Start now. Embark on that new venture. Do what makes you happy. Keep the joy.

Have a wonderful day beautiful Divas. “All is well”.

How do you keep your joy? (Read more.)

Thursday, October 25, 2018

Beyond Borscht

Russian cuisine in London. From The Spectator:

If the idea of Baltic herrings muffled in beetroot sounds a little too authentic, there are places which straddle the East-West divide. Bob Bob Ricard in Soho is one of them. Bob Bob Ricard rolls with a much loucher crowd than Stolle and on the inside looks a little like Baz Luhrmann’s Deco rendering of Gatsby Manor. The food, which seeks to find common ground between Russian and western European cooking, is nice if not spectacular. What you pay for is the trimmings, which include a personal champagne button at every table. You might say it’s gauche. In certain quarters of Moscow’s richest districts, it’s the new authentic. Across town, on the edge of London Fields, is Zakuski, which on Saturdays sells a range of flavoursome and reworked Russian salads from a stall in Broadway Market, as well as catering for events. The word zakuski is normally translated into English as ‘starter’, but for Russians it is something closer to the Swedish idea of a smorgasbord, whereby one takes a little from a range of hot and cold dishes. Salads play a starring role in many Russian smorgasbords and the stall serves the best of them, along with a few fusion variants. On a recent visit I had a salad with beetroot, walnut and prune and another with aubergine, tahini and garlic. (Read more.)Share

‘Leeching Off Their Husbands’

Democratic Senate candidate Kyrsten Sinema, of Arizona, once described stay-at-home moms as leeches in a 2006 interview. “These women who act like staying at home, leeching off their husbands or boyfriends, and just cashing the checks is some sort of feminism because they’re choosing to live that life,” she told Scottsdale nightlife magazine 944. “That’s bullshit. I mean, what the f*** are we really talking about here?"

Sinema, who has come under fire recently for making derogatory comments about Arizona in newly resurfaced videos, also once described conservatives as “Neanderthals.” In one video, Sinema is seen grimacing and shaking her head after saying that she ran for a position in the Arizona state legislature. (Read more.)

Meanwhile, single motherhood is becoming more common by the day, which appears to be favored by socialism, because then the government takes the place of the father. From Bloomberg:

An increasing number of births happen outside of marriage, signaling cultural and economic shifts that are here to stay, according to a new report from the United Nations. Forty percent of all births in the U.S. now occur outside of wedlock, up from 10 percent in 1970, according to an annual report released on Wednesday by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the largest international provider of sexual and reproductive health services. That number is even higher in the European Union. (Read more.)

Socialism and civil liberties do not mix. From Reason:

In 1981, the socialist economist and best-selling author Robert Heilbroner took to the pages of the democratic socialist magazine, Dissent, to answer what would seem like a rather academic question, "What is Socialism?" His answer was a raw, honest, and devastating critique of democratic socialism from a man wrestling with his faith. In his essay, Heilbroner—reminiscent of a similar definitional debate today among progressives and socialists—explained that socialism is not a more generous welfare state along Nordic lines. Instead, it is something entirely different, an economic and cultural configuration that suppresses if not eliminates the market economy and the alienating and selfish culture it produces.Share

"If tradition cannot, and the market system should not, underpin the socialist order, we are left with some form of command as the necessary means for securing its continuance and adaptation," Heilbroner wrote. "Indeed, that is what planning means. Command by planning need not, of course, be totalitarian. But an aspect of authoritarianism resides inextricably in all planning systems. A plan is meaningless if it is not carried out, or if it can be ignored or defied at will."

As Heilbroner reluctantly acknowledged, socialist planning cannot co-exist with individual rights, an achievement of Western culture he wanted to preserve. Instead, under socialism, culture must produce "some form of commitment to the idea of a morally conscious collectivity." This, however, was antagonistic to "bourgeois" culture, which "encourages and breeds the idea of the primary importance of the individual." And bourgeois culture, devoted to the sovereignty of the individual, he wrote, "naturally asserts the rights of individuals to speak their minds freely, to act as they wish within reasonable grounds, to behave as John Stuart Mill preached in his treatise On Liberty." A socialist culture, Heilbroner feared correctly, couldn't abide this "celebration of individualism" because it is "directly opposed to the basic socialist commitment to a deliberately embraced collective moral goal." (Read more.)

The Case of Jane Doe Ponytail

ShareFor years now, Flushing has been an ever-replenishing repository of immigrants entangled in the underground sex economy. The commonplace raids of illicit massage operations across the country routinely lead to the arrests of women with Flushing addresses. These parlors disappear and reappear with regularity, undermining the police crackdowns often prompted by neighborhood complaints. The industry’s opaqueness adds to the confusion. Some parlors have legitimate state licenses; some legitimate operations have masseuses making sex-for-money side deals; and some are illegally unlicensed, with no interest at all in addressing someone’s sore neck.Emotionally manipulated by their bosses, ashamed of what they do, afraid to trust, the women rarely confide in the police or even their lawyers about their circumstances. They might be supporting a family in China, or paying back a smuggling debt, or choosing this more profitable endeavor over, say, restaurant work. No matter the backstory, the police say their collective silence further complicates law-enforcement efforts to build racketeering and trafficking cases against the operators. But society has become increasingly aware of the complexities and inequities of the commercial sex economy, including a criminal justice system that has tended to target the exploited — often immigrant women and members of the transgender community — while rarely holding accountable their customers and traffickers.In early 2017, New York’s police commissioner, James O’Neill, announced at a news conference that he would redirect his vice division to address prostitution and sex trafficking. This would include training intended to alter what he called the “law-enforcement mind-set.”“We’ve already switched much of our emphasis away from prostitutes, and begun focusing much more on the pimps who sell them and the johns who pay for their services,” he said. “Like all crime, we can’t just arrest our way out of this problem.”Since the establishment of this new “mind-set,” the police have continued to struggle at building criminal cases against the operators. But prostitution arrests in New York City have dropped more than 20 percent in the last year, while the arrests of customers have spiked. Still, this change in attitude at Police Headquarters in Lower Manhattan had not necessarily crossed the East River to benefit an immigrant now lying on her side, unable to speak, gazing up at a plainclothes officer trying to calm her until an ambulance arrived. Beside a spent cigarette, her blood pooled on the pavement she had so often worked.By morning, Song Yang would be dead, shattering a tight Chinese family that would never accept the police version of events. Her death would also come to reflect the seemingly intractable nature of policing the sex industry, and cast an unwelcome light on the furtive but ubiquitous business of illicit massage parlors. (Read more.)

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

The Girl with the Seven-Pointed Star

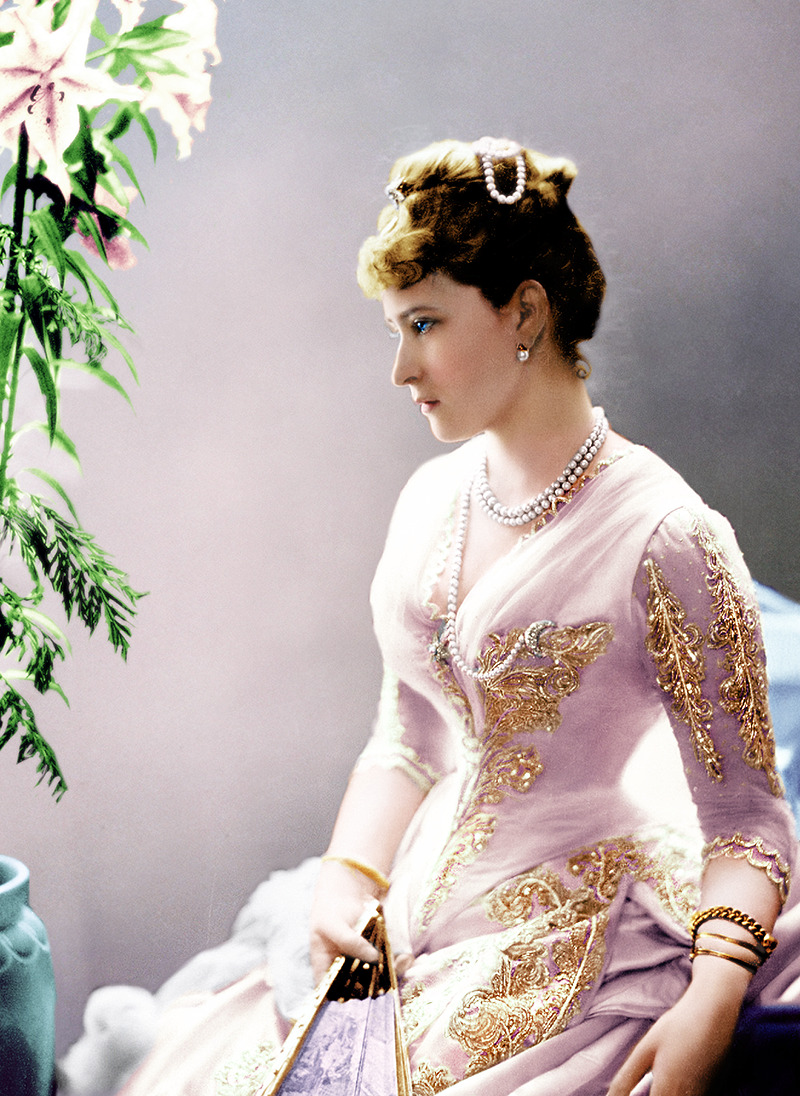

May I present Miss Jeanette Jerome, barely twenty years old, living in Paris and newly-engaged to Lord Randolph Churchill, the younger of the Duke of Marlborough's two sons? She's American. Privileged. Staring down her future with deadly purpose. It's a beautiful face, certainly, but grave and also haunting. In her black hair she has clipped a seven-pointed diamond star lent to her by her mother--probably in celebration of the engagement, and Jennie's transition from girl to woman. I'm guessing the pearls were a gift from her father, because pearls were suitable for debutantes and Leonard Jerome always knew what his girls liked. Jennie assumes she'll have lots of jewels to wear in future. She thinks a life of glamor and adventure lies ahead. She's right; but her husband's funds are never enough to bankroll her style, and the seven-pointed star remains her one flashing ornament. Until her mother takes it back, to give to Jennie's little sister, when Leonie in turn is betrothed. The star was probably fashioned by Louis-Francois Cartier, founder of Cartier jewelers. But that's my guess. Nobody really knows. Louis-Francois worked in an atelier next door to Charles Frederick Worth's fashion salon in Paris, where Jennie's trousseau was made. When wealthy clients demanded it, Worth's craftswomen embroidered gems in elaborate designs on their silk gowns--and Cartier supplied the stones. Eventually his clientele was broad and deep and wealthy enough that he opened a store of his own. (Read more.)More HERE. Share

Illegal Caravans

Just in time for the midterms, another "spontaneous" migration from Central America began with a bevy of allegedly oppressed and downtrodden Hondurans leading the way. Pressured by a threat from President Trump to cut aid to Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador if the caravan is not stopped, some moves by these governments have been made. Yet evidence exists that these migrations are not spontaneous, with both of the governments in question encouraging them as a political and economic safety valve and a source of foreign currency, financed in part by foreign leftists with connections to George Soros.

As Fox News's Laura Ingraham noticed in a tweet, this is not a walk in a national park, but an expensive and arduous journey:

Who is funding the migrant "caravan"? Each migrant's passage can cost as much as $7K each. Per capita income Honduras is $2.3 K.

It is doubtful that such sums came from the kiddies' college funds. Evidence of Soros funding of an earlier "spontaneous" migration have been found among the tentacles of support that flow from his Open Society group coffers:

Leftist billionaire George Soros is funding the well-organized anti-Trump migrant caravan invasion from Central America that has been hitting the United States-Mexico border in defiance of immigration enforcement.Several major ultra-liberal foundations and corporations have supported the asylum-seeking migrant caravans, and Soros' funding has been tied to several groups that have spearheaded the "refugee" invasion coalition – also dubbed "the Soros Express."

"The caravan is organized by a group called Pueblo Sin Fronteras, [b]ut the effort is supported by the coalition CARA Family Detention Pro Bono Project, which includes Catholic Legal Immigration Network (CLIN), the American Immigration Council (AIC), the Refugee and Immigration Center for Education and Legal Services (RICELS) and the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) – thus the acronym CARA," WND reported. "At least three of the four groups are funded by George Soros' Open Society Foundation."The hands of the Honduran government are not clean in these efforts. Among the alleged asylum-seekers parked on the U.S. border is a contingent of Hondurans, allegedly fleeing persecution, poverty, crime, and oppression. If that is the case, why is the Honduran government helping them, driving them northward under orders given to the Honduran ambassador, who is helping and escorting them?

Leaders of a caravan of Central American migrants traveling toward the United States through Mexico have repeatedly accused the Honduran government of corruption and with failing to address the poverty, crime and economic conditions forcing families to flee by the thousands.

So it shocked some observers when the Honduran ambassador joined the migrants protesting outside the Honduran embassy in Mexico City on Wednesday, and then accepted their invitation to walk 9 miles to a migrant shelter.

"I have been ordered by my government to support the Honduran migrants traveling with the caravan. There are about 200 Hondurans who we will help out with paperwork and whatever is necessary," Alden Rivera Montes, the Honduran ambassador to Mexico, told El Universal. (Read more.)

Criminals are traveling with them. From Townhall:

Violent transnational crime organizations like MS-13 have used the never ending illegal immigration crisis in the past to smuggle gang members. The organization has also used detention centers to recruit unaccompanied minors into the gang. According to Border Patrol sources, violent MS-13 gang members are using the Nogales processing center in Arizona as a recruitment hub and as a transfer point for gang members to get into the United States. The Red Cross has set up phone banks inside the processing center so unaccompanied minors can make phone calls to family members inside the United States and back home in Central America. According to sources, those phones are also being used by MS-13 members to communicate with gang members already in the United States and operating in cities like Atlanta, New York and Chicago. Further, many teenaged males inside the facility have approached Border Patrol agents and have said gang members have tried to recruit them from shared cells. (Read more.)

From Ben Shapiro at Daily Wire:

But just because there are millions of people across the world who would love to enter the United States for purposes of finding work does not mean that the United States has either the resources or the responsibility to open its borders to all comers. As a libertarian on the flow of labor, I have no problem with people coming to the United States to work – but there are obvious economic costs associated with unchecked illegal immigration in a welfare state. Furthermore, the failure of the United States to assimilate new immigrants has increased radically in recent years with the rise of a multicultural ethos on the political Left. To suggest that the United States leave its borders wide open to anyone wanting to enter is to suggest national suicide, as it would be for any nation. (Read more.)

Meanwhile, a second caravan is gathering in Guatemala. From Fox News:

A second migrant caravan is forming at the Honduran border and is expected to follow the larger caravan of more than 7,000 from Central America towards the U.S.-Mexico border, The Wall Street Journal reported on Tuesday. The remaining migrants in the first group are about 1,100 miles from the border town of Reynosa, which is across from McAllen, Texas, the paper reported. Guatemalan authorities on Sunday estimated the new group -- which gathered in a Guatemalan city near the border of Honduras -- to be at 1,000. But the group appears to be growing. The Journal, citing estimates from church-run charities and activists, reported that the group is now made up of about 2,500. By Monday evening the group had entered the eastern Guatemalan town of Chiquimula. (Read more.)Share

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)